humanoid supremacy is wrecking the planet

Medium | 31.12.2025 08:52

humanoid supremacy is wrecking the planet

Follow

9 min read

·

Just now

Listen

Share

The Bee-holders: We’ve spent centuries looking for wonder in humanoid forms while the real sorcery was wearing stripes all along.

I used to think I understood magic. I’d collected every fairy tale, every myth about ethereal beings who granted wishes and transformed pumpkins into carriages. I knew the stories so well I could recite them—beautiful, human-like creatures with gossamer wings, always just our size, always speaking our language, always invested in our human dramas. It wasn’t until I watched a bee navigate back to its hive after foraging miles away, using the sun as a compass and performing a dance to communicate precise locations to its sisters, that I realized I’d been looking for magic in all the wrong shapes.

We've made a devastating mistake, one that's quite literally killing us: we've conflated "powerful" with "looks like us."

The Fairy Fallacy

Consider what we’ve asked of fairies in folklore. They pollinate our crops (no, wait—that’s bees). They create intricate, architecturally impossible structures (that’s also bees). They work collectively for the survival of their community, transforming raw materials into liquid gold (honey, actually). They’re essential to the ecosystem’s survival, and their disappearance would trigger agricultural collapse.

But fairies get the storybooks. Bees get pesticides.

Fairies, even at their most alien, are modeled after us. Tiny humans with wings. Tinkerbell throwing pixie dust tantrums. The good fairy godmother in Cinderella who manifests exactly when the plot requires emotional resolution. We’ve wrapped our wonder in a package that resembles our reflection because we cannot fathom that intelligence, beauty, or necessity might exist in forms that don’t validate our own.

This is the narcissism that’s rendered us unable to see magic, genius, or divinity in anything that doesn’t mirror our most conventional expectations.

The Unbearable Whiteness of Being Divine

I grew up with a white Jesus on the wall, Nordic-looking and blue-eyed, gazing benevolently from above the mantle. No one had to tell me this was historically absurd—a Middle Eastern Jewish man reimagined as a Scandinavian shepherd.

When Europeans repainted divinity in their own image, they didn't just commit an act of historical revisionism. They performed a spell—the darkest kind—that said power, goodness, and godliness all had one acceptable aesthetic. Buddha became lighter-skinned in Western depictions. Egyptian deities, originally depicted with brown skin, were gradually whitewashed in popular culture. Even the angels got the treatment, transformed from the bizarre, many-eyed cosmic entities described in religious texts into beautiful white humans with feathered wings.

The pattern is unmistakable: we'll worship it if it looks like us. Or more precisely, if it looks like what dominant powers have decided "us" should look like.

This rebranding has consequences beyond representation. When we make the divine humanoid—and specifically, when we make it conform to Western beauty standards—we severe our connection to the actual forces that sustain us. We start believing that a bearded man in the sky is more worthy of devotion than the mycelial networks beneath our feet that allow trees to communicate and share resources. We pray to human-shaped gods while ignoring the ocean that produces most of our oxygen.

We've committed the cardinal sin of narcissism: mistaking our reflection for the source of life itself.

The Genius We Refuse to See

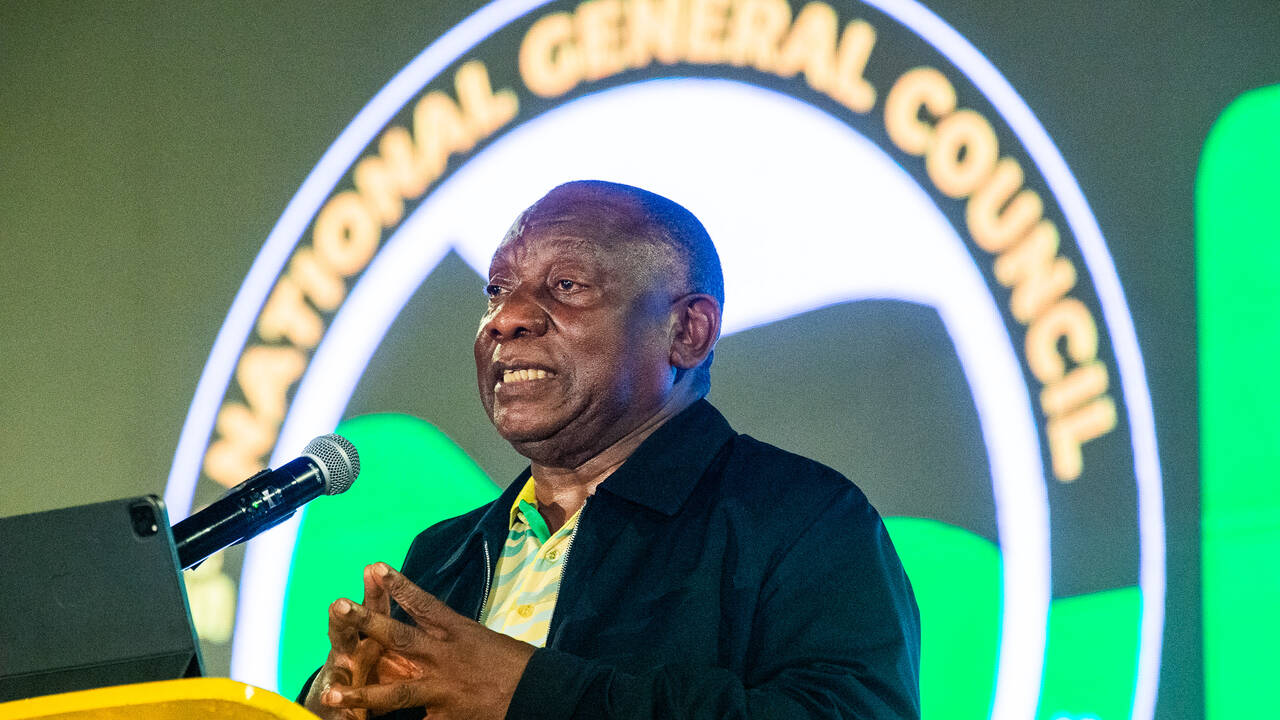

This same pattern plays out in how we recognize human brilliance. We know this story; we've lived it, watched it, perhaps perpetuated it. Genius, in our collective imagination, looks a certain way. It's Einstein with wild white hair. It's Steve Jobs in a black turtleneck. It's the disheveled white man in a laboratory or the Silicon Valley founder who dropped out of Harvard.

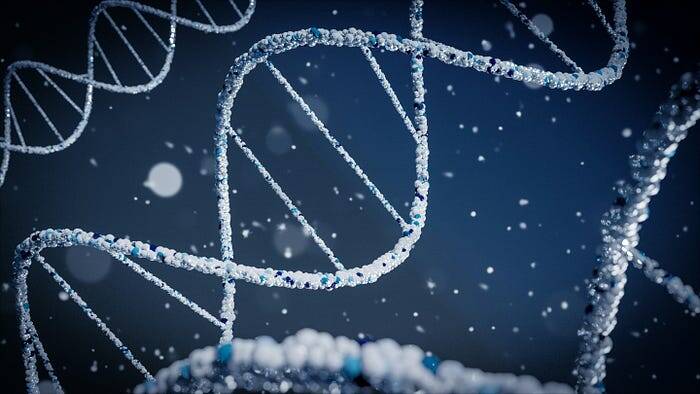

When Katherine Johnson calculated the trajectories that put humans on the moon, her genius was invisible for decades—not because it wasn't extraordinary, but because a Black woman performing mathematical sorcery didn't match our preconceived image. When Rosalind Franklin's X-ray crystallography revealed the structure of DNA, her contribution was minimized and attributed to the men who used her data. The pattern holds: If genius doesn't arrive in the expected package, we struggle to recognize it, even when it's changing the world.

I think about Octavia Butler, who had to fight for every inch of recognition in science fiction—a genre that claimed to be about imagining alternative futures while struggling to imagine that a Black woman could be its prophet. I think about how many medical innovations from non-Western cultures were dismissed as "primitive" or "folk remedies" until white researchers could repackage and patent them.

The cost of this myopia isn't just social injustice—though that would be enough. The cost is that we're flying half-blind, ignoring vast repositories of knowledge, innovation, and wisdom because they don't arrive wearing the face we've been taught to trust.

The Deity We’ve Forgotten to Worship

We’ve spent millennia creating elaborate mythologies about humanoid gods and goddesses—beings we must appease, worship, and obey—while living on an actual deity that we treat like dirt. Literally.

The Earth is not a metaphor. It's not a symbol or a poetic device. It's a powerful, complex, responsive system that regulates temperature, cycles water, generates oxygen, and hosts the only known life in the universe. It performs daily miracles we've learned to ignore: photosynthesis turning light into food, mycorrhizal networks sharing nutrients between species, oceans absorbing carbon and producing weather patterns.

Get Celia Solstice’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

If a humanoid figure showed up and offered these gifts, we'd build temples. We'd write scripture. We'd dedicate our lives to service and gratitude.

Instead, we extract, we dump, we pave, we pollute. We treat the actual source of our existence with less reverence than we show to marble statues and ancient texts.

The disconnection isn't accidental—it's baked into how we've imagined the sacred. When we made gods in our image, we implicitly downgraded everything that wasn't our image. Trees became resources instead of relatives. Rivers became property lines instead of living arteries. Animals became food, entertainment, or pests instead of other nations with whom we share this planet.

We expelled ourselves from Eden not because we ate from the tree of knowledge, but because we stopped seeing the tree as worthy of knowing.

Every Movement Must Be an Environmental Movement

I've been part of various social justice efforts over the years, and I've noticed a troubling pattern: environmentalism is often treated as a separate concern, something we'll get to after we handle the "real" issues of human rights, economic justice, or political reform.

This is like saying we'll worry about the foundation after we've finished decorating the upper floors.

There is no racial justice on a dying planet. There is no gender equity in climate collapse. There is no workers' rights when crops fail and water sources dry up. The environmental crisis isn't adjacent to social justice—it's the context in which all other justice must operate.

And yet, we've trained ourselves to view "the environment" as something separate from us, something "out there" that naturalists and hippies worry about while the rest of us focus on serious human concerns. This too is humanoid supremacy: the delusion that human society exists independently of the ecosystems that sustain it.

Indigenous communities have been trying to tell us this for generations. They've watched as dominant cultures destroyed watersheds, clearcut forests, and extracted minerals, all while dismissing Indigenous resistance as primitive or anti-progress. But Indigenous knowledge systems—which recognize humans as one part of an interconnected web—consistently prove more sophisticated than the reductionist models that treat nature as a machine we can endlessly exploit.

The supremacy of humanoid thinking has made us stupid. It's made us believe we can survive the death of the systems that feed us, clothe us, and literally produce the air we breathe.

To See Magic Again

So how do we undo this? How do we retrain our eyes to see wonder in forms that don't mirror our own?

It starts with humility. It starts with admitting that we’ve been wrong about what constitutes intelligence, beauty, and value. It means recognizing that a bee’s navigation system is more sophisticated than most human-made GPS. That trees have been networking for millions of years before we invented the internet. That the Earth’s climate regulation is more complex than any system we’ve engineered.

It means looking at people whose faces don't match the default settings of "genius" or "leader" or "expert" and actually listening instead of waiting for them to perform credibility according to our narrow standards.

It means, quite literally, getting down on our knees and putting our hands in the dirt. Touching the earth. Watching what lives in it. Learning the names of plants and insects in your bioregion. Understanding that these aren’t background scenery for human drama but the actual protagonists of the only story that ultimately matters.

I've been trying to do this myself, awkwardly and imperfectly. I'm learning to notice when I'm looking for human-shaped solutions to problems that require different thinking entirely. I'm practicing recognizing expertise in elders, in Indigenous knowledge keepers, in people whose genius was never credentialed by institutions designed to exclude them. I'm trying to see my own species as one species among millions, remarkable but not exceptional, part of something rather than the point of everything.

It's uncomfortable work. It requires surrendering the flattering story that we're the main characters, the pinnacle of creation, the ones for whom all of this exists.

I’ve found a kind of relief in that discomfort. The weight of believing we’re central to everything is exhausting. There’s freedom in being part of something larger, in recognizing that the magic we’ve been seeking has been here all along—not in beings made in our image, but in the actual, existing wonder of a world we’ve barely begun to understand.

The bee returns to its hive, heavy with pollen, and performs its dance. The other bees watch, interpret, and fly off in the direction indicated. They're speaking in vectors and angles, in the language of solar navigation and collective intelligence.

There are no words for this in fairy tales. No storybooks celebrate this everyday sorcery. We've been so busy imagining magic in humanoid forms that we've missed the real thing buzzing past our heads, keeping us alive, asking nothing in return but that we stop poisoning them.

May be the real magic is the ability to recognize wonder without needing it to wear our face. The capacity to love what doesn’t love us back in ways we recognize. The wisdom to know that the most powerful forces in the universe don’t need our validation—but we desperately need their survival.

I used to think I understood magic. Now I’m learning to see it. And it turns out it was never about believing in fairies. It was about believing the bees were worth saving.