5 Ways Politicians Have Been Manipulating Voters Since Ancient Rome

Medium | 19.01.2026 19:09

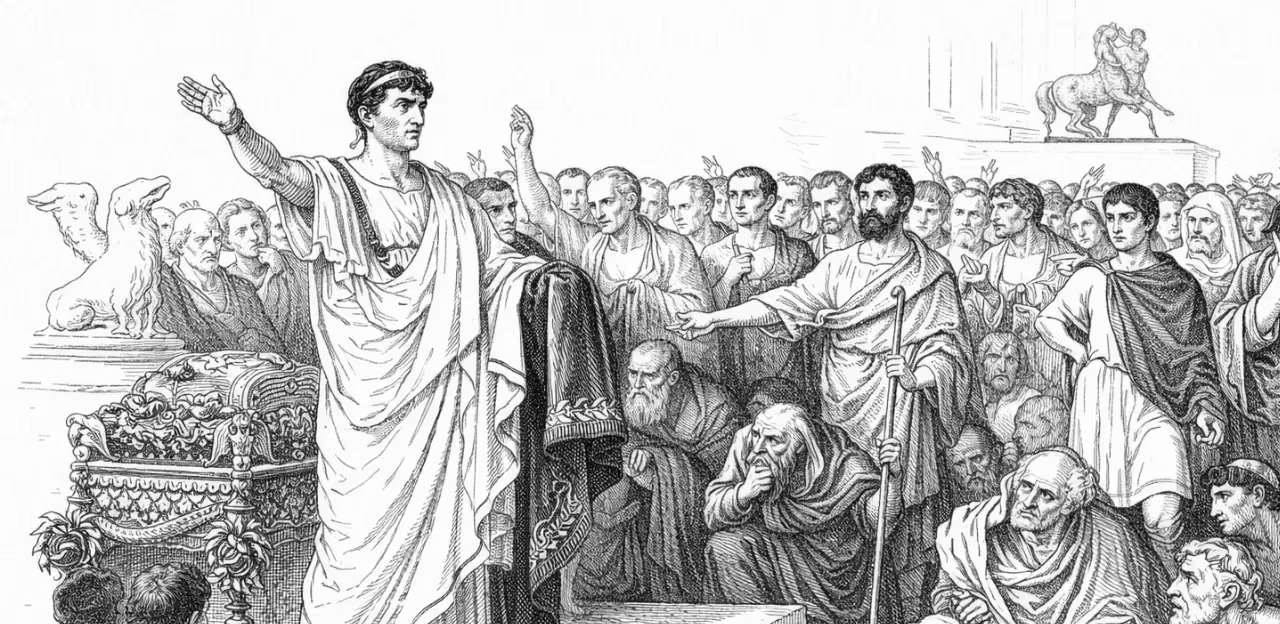

5 Ways Politicians Have Been Manipulating Voters Since Ancient Rome

If these worked in 64 BC, imagine how well they work on us now

6 min read

·

Just now

--

Listen

Share

Every election campaign promises to be different…

But it always feels the same.

The rehearsed smiles return, the impossible promises, and that sudden closeness from politicians who never listened to you and who now seem to understand you better than anyone. You’ve seen this movie too many times to be surprised by the ending. And yet, something inside you wants to believe. It’s not that you’re naïve — it’s that it’s designed to activate hope rather than memory.

And the most uncomfortable part is that this is not new; it’s ancient. Very ancient…

In 64 BC, in the heart of the Roman Republic, the exact manual for these modern spectacles already existed: the Commentariolum Petitionis (“Handbook for the Candidate”). It was written by Quintus Tullius Cicero to help his brother Marcus Tullius Cicero win the election to the Roman consulship. And no, it didn’t talk about ethics or good governance — it talked about persuasion and emotions.

Read today, it sounds uncomfortably current.

Let’s analyze, point by point, the five tactics that were already being used back then to manipulate the masses… and that we continue to applaud every time there are elections.

1. Promise everything, deal with it later

Promising everything is a political tactic designed to strike the emotions of the masses.

Quintus advised his brother this way: people prefer to hear an impossible promise rather than an honest silence. Promises calm people, because uncertainty about the future frightens them. Painting a bright future activates the voter’s imagination.

The promise doesn’t matter.

What matters is giving people the feeling that someone is taking charge of the future.

That’s why electoral programs are filled with unrealistic goals and inflated figures. Yesterday, land, positions, or protection were promised; today, it’s jobs, prosperity, and stability. The promise is collective anesthesia: it reduces anxiety, even if it doesn’t cure the disease.

And when the failure to deliver arrives, there will always be a better excuse than telling the truth.

2. Favors never expire, they are always collected

Politics, behind its façade, is a marketplace of debts and favors.

Quintus advised his brother to keep track: who owed him a favor, who had been helped, who could return the favor now. And if someone owed him nothing, no problem — it was enough to hint that they might receive something later if they helped him now to win the election.

Support is never free; it’s just paid at different times and in different forms.

What today we call “networking,” “revolving doors,” or “influence peddling” is the same ancient trade in favors, just with a more technical name.

You win when you know exactly whom to call and what to remind them of.

Today for you, tomorrow for me.

3. Attack your rival where it hurts most

This is where the art of negative politics is officially born.

Quintus did not advise his brother to debate ideas; on the contrary, he recommended pointing out personal weaknesses: scandals, mistakes, inconsistencies. The goal was not to convince voters that you were better — it was to distract them from any merit your rival might have.

If you keep the spotlight on your opponent’s dirt, no one will trust their proposals.

Since then, politics has learned that scandal sells better than rational proposals. Noise is more effective than reasoned discourse. It’s easier for the masses to hate than to think, so arguments and data become unnecessary.

Don’t give arguments to be elected.

Give reasons to hate your opponent.

4. Make the voter feel special

Flattery is mandatory.

Quintus advised his brother to do something that borders on psychopathy: during the campaign, you must pretend to care. Listen, nod, smile, radiate warmth, remember names. The voter is going to be represented by the politician — you must identify with the voter as much as possible.

Even if it’s fake and only for a moment…

For a few weeks, the citizen becomes the protagonist of the story. Their problem matters; everyone wants to hear their opinion. Then, after the ballots are cast, administrative silence arrives. But by then, the effect has already done its job.

It’s like Carnival: one day a year the king dresses as a beggar and the beggar dresses as a king…

only so that for the rest of the year everything stays the same.

5. Hope and fear as political products

It’s not about convincing with arguments — it’s about making people feel.

Even the most skeptical voter needs to cling to the idea that this time it will work. Hope and fear are sold as emotional products: a better tomorrow, an imminent change, an approaching threat that only you, as a politician, can prevent…

Quintus knew it: whoever manages to embody that hope or promise salvation gains loyal followers, even if only until after the victory. Voter disappointment is a later cost that all politicians already accept.

But nothing happens — hope and fear are renewed every four years.

From the Roman Republic to modern politics, not much has changed…

Want to know more? Here are three related ideas to go deeper:

- The 10 most dangerous logical fallacies (and how to avoid them)

- The 6 fundamental laws of persuasion

- The world is not as bad as they paint it

✍️ Your turn: If these tactics have worked for more than 2,000 years, what does that say about politics… and what does it say about us as citizens?

💭 Quote of the day: “To lose the possibility of something is the same as losing hope, and without hope nothing can survive.” — Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

🌱 Here I plant ideas. In the newsletter, I make them grow.

Daily insights on self-development, writing, and psychology — straight to your inbox. If you liked this, you’ll love the newsletter. 🌿📩

👉 Join 50.000+ readers: Mental Garden

See you in the next letter, take care! 👋

References 📚

- Quintus Tullius Cicero. Commentariolum Petitioni