Highly Educated but Underutilized

Medium | 30.12.2025 03:47

Highly Educated but Underutilized

3 min read

·

1 hour ago

--

Listen

Share

Foreign Professionals in Finland

Finland is home to a growing number of foreign-born professionals whose skills are often underutilized despite high levels of education. Structural and social barriers continue to limit their full integration into the labor market, leaving many highly qualified migrants in positions that are far below their capabilities.

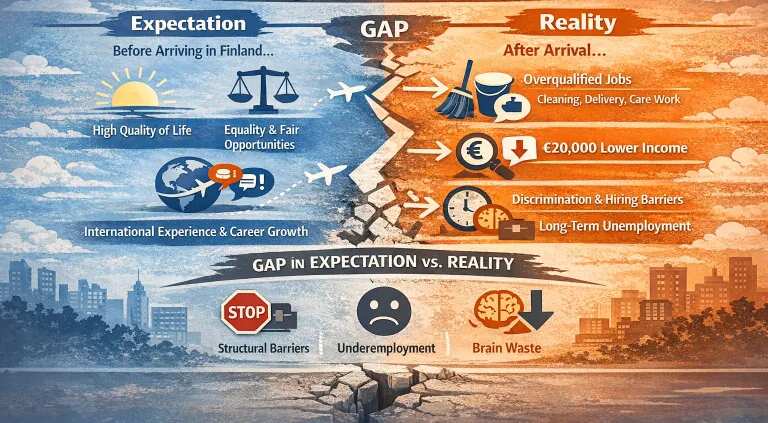

Foreign-born workers are particularly overrepresented in sectors such as cleaning (~32–40%), personal care, and platform-based food delivery services (Statistics Finland, Zenodo, 2024). Despite high tertiary education rates — around 40% of 25–54-year-olds with foreign backgrounds — many migrants experience “brain waste,” with overqualification rates of around 36%, roughly double those of native workers (OECD, Statistics Finland, 2024). Discrimination compounds the problem: applicants with foreign names receive fewer callbacks, and foreign-born professionals frequently report bias in hiring and workplace practices (Valtioneuvosto).

OECD reports and academic studies show that skilled migrants often work below their qualifications due to credential recognition, language, and labor-market barriers (OECD, Skills and Labour Market Integration). Even doctoral graduates may find themselves in insecure or non-academic roles. In regulated professions, lengthy licensing procedures — especially for doctors and nurses trained outside the EU/EEA — force many into lower-paid or unrelated roles during re-qualification (Valvira guidance; studies on internationally educated nurses in Finland).

Studies further show that highly educated immigrants are more likely to be employed in fixed-term or part-time positions that fail to utilize their expertise (Nichols et al., TEK; Mutuku, 2017, Theseus). Dr. Elli Heikkilä notes that refugees with tertiary education often work in clerical, service, or manual jobs. Individual experiences, like that of Umer Javaid — a master’s graduate in logistics and electrical engineering with nine years’ experience — illustrate the mismatch: “Even when I explained my background, they said the only training available for foreigners was in cleaning” (Javaid).

Recent reports (2024–2025) indicate that over-education and under-employment among highly skilled technical workers have increased.

TEK surveys highlight unemployment and long unemployment spells among international technology experts (TEK; Työn ja talouden tutkimus LABORE). Immigrants are also over-represented in accommodation, food services, and care sectors regardless of education level (Statistics Finland). In healthcare, migrant physicians often occupy primary care or on-call roles, report lower well-being, and are less likely to hold leadership positions (European Journal of Public Health, OUP Academic).

Labore’s 2024 survey of 702 PhD holders found that foreign-origin graduates face long-term unemployment and systemic barriers. On average, they earn €20,000 less per year than Finnish-origin peers, despite similar qualifications (Labore, 2024). Job security remains precarious: only about two-thirds of experts from outside Europe have permanent contracts, and nearly one-third experienced unemployment within the past three years (TEK, 2025).

Before coming to Finland, many foreign-born professionals held positive expectations of the country, anticipating a high quality of life, equality, and opportunities to gain international experience and develop communication skills (Kristelstein-Hänninen, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences, 2025). These expectations often clash with the reality of underemployment, discrimination, and integration barriers they encounter.

Finland benefits from a highly skilled migrant workforce, yet discrimination, structural barriers, and inadequate integration services push many into low-paid, low-skill jobs. Addressing these issues is essential — not only for fairness but also to fully harness the potential of international talent in the country.