Revolution and the Problem of Premature Equality

Medium | 23.12.2025 03:57

Revolution and the Problem of Premature Equality

Follow

5 min read

·

Just now

Listen

Share

Revolution and the Problem of Premature Equality

Revolutionary movements often discover that political victory and formal equality do not automatically produce satisfaction, stability, or sustained progress. Many revolutions that dismantled capitalist relations and abolished exploiting classes later confronted stagnation, popular discontent, and pressure to retreat from egalitarian commitments. This outcome is not a moral failure or a lack of revolutionary will. It is a structural problem rooted in material conditions: equality imposed on underdeveloped productive forces generates its own form of dissatisfaction.

This conclusion is not external to Marxism. It is demanded by Marxism itself.

Equality, Scarcity, and the Social Nature of Dissatisfaction

Capitalism produces dissatisfaction through inequality, but equality does not eliminate dissatisfaction when achieved under conditions of scarcity. Human satisfaction is fundamentally social and comparative, and comparison does not stop at national borders.

An egalitarian but poor society may eliminate internal inequality, yet it intensifies external comparison. People do not compare themselves with the poor of other countries, but with the elites of richer societies, whose lifestyles are globally visible. Equality at home therefore coexists with frustration about collective deprivation relative to what exists elsewhere.

The question shifts from “Why does my neighbor have more?” to “Why do we all have so little compared to what is possible?” Equality resolves internal comparison but fails external comparison, producing persistent dissatisfaction even in the absence of domestic inequality.

Marx anticipated this problem with absolute clarity. In The German Ideology, he wrote:

“This development of productive forces is an absolutely necessary practical premise, because without it want is merely made general, and with want the struggle for necessities begins again, and all the old filthy business would necessarily be restored.”

Scarcity does not disappear through equalization. It reproduces competition, resentment, and regression in new forms.

Socialism Is Not the Equal Distribution of Poverty

Scientific socialism has never meant the equal distribution of scarcity. Marx and Engels conceived socialism as the rational organization of abundance made possible by advanced productive forces.

Marx reiterates in Capital:

“The distribution of the means of consumption at any time is only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production themselves.”

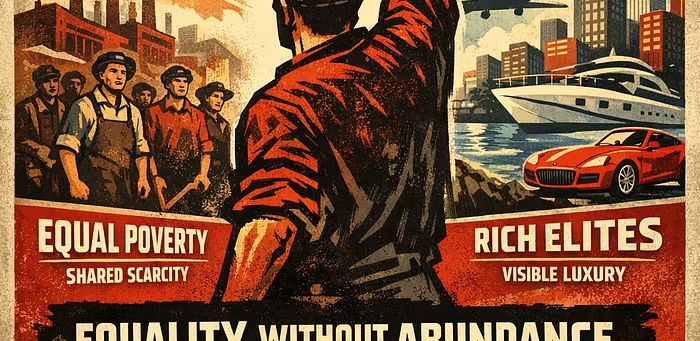

Distribution cannot compensate for underdeveloped production. When productive forces are weak, equality means shared poverty. Justice may be formally achieved, but aspirations remain unmet. Premature equality — equality without abundance — creates structural dissatisfaction rather than stability.

Engels consistently warned against turning equality into an abstract moral principle detached from material conditions. In Anti-Dühring, he observed:

“The demand for equality in itself, in its abstract form, is nothing but the old cry of the bourgeois revolution.”

For Engels, socialist equality becomes meaningful only when grounded in productive capacity sufficient to sustain abundance.

The Structural Limits Faced by Revolutions in Poor Countries

Get Lumpen Comrade’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Revolutions in underdeveloped societies therefore face recurring and predictable problems:

- Slow growth due to limited productive capacity

- Popular dissatisfaction driven by global comparison

- Pressure to reintroduce inequality as a means of growth

- Brain drain and external dependence

These outcomes are not ideological failures. They are the material consequences of attempting egalitarian distribution without a productive base capable of sustaining it.

Lenin confronted this reality directly during the crisis following the Russian Revolution. Defending the New Economic Policy in The Tax in Kind, he stated:

“Socialism cannot be built on poverty. We must raise the productive forces to a level higher than that achieved by capitalism.”

The NEP was not a retreat from socialism but an acknowledgment of material reality: productive forces must be developed first, even at the cost of temporary inequality. Equalizing poverty was not socialism; it was stagnation disguised as principle.

The Development Imperative and Objective Economic Laws

From this follows a decisive conclusion: the development of productive forces is the first and non-negotiable imperative of any socialist project.

Stalin formulated this with clarity in Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR:

“Man may discover these laws, get to know them and, relying upon them, utilize them in the interests of society; but he cannot destroy them or create new economic laws.”

Among these objective laws is the primacy of production over distribution. Stalin further insisted:

“The fundamental economic law of socialism consists in ensuring the maximum satisfaction of the constantly growing material and cultural needs of the whole of society through the continuous expansion and perfection of socialist production.”

Scarcity cannot be abolished by decree. Sanctions, trade restrictions, technological blockades, and imperialist pressure do not suspend economic laws. They are permanent features of the world system.

There is no Marxist justification for treating external constraints as an alibi. Imperialist pressure is not an exception; it is the normal environment in which socialism must operate. Development is therefore non-negotiable.

Revolution Is the Beginning, Not the End

The real historical challenge for Marxists begins after the seizure of power. Revolution does not dissolve global hierarchies, neutralize scarcity, or generate abundance automatically through the abolition of the exploiting class.

Post-revolutionary politics is not the administration of a completed victory, but the difficult task of construction under hostile conditions. Finding a path through sanctions, isolation, technological dependence, and so on is the challenge waiting for a Marxist revolutionary ,post revolution.

To assume that revolution itself resolves these contradictions is to lapse into voluntarism. Marxism has never claimed that the destruction of class relations instantly abolishes material constraints. On the contrary, it insists that social transformation must work through objective conditions, not against them.

A revolution that fails to develop productive capacity risks converting liberation into stagnation. A Marxism that treats external pressure as an excuse rather than a problem to be overcome abandons materialism for consolation.

Conclusion

The problem of premature equality is not an argument against socialism. It is a warning issued repeatedly within Marxism itself.

Equality without abundance risks becoming shared deprivation rather than collective liberation. Without developed productive forces, justice remains formal and dissatisfaction persists.

Sustainable revolution requires uniting equality with productive development. The abolition of exploitation is only the beginning. What follows is the far more difficult task: building abundance in a hostile world.

Only when productive forces are sufficiently developed can equality overcome both internal and external comparison — transforming shared poverty into shared prosperity, and justice in principle into satisfaction in practice.

As Marx warned long ago, “all the old filthy business” returns — no matter how revolutionary the intentions.