Palestinians forced from West Bank refugee camps left in limbo as Israeli demolitions go on

BBC | 22.11.2025 02:24

"They punished ordinary people. This is collective punishment."

It's been more than nine months since 54-year-old Nehaya al-Jundi last saw her home in the Palestinian refugee camp of Nur Shams, in the occupied West Bank, after being forced to evacuate by the Israeli military.

"They punished the infrastructure, the institutions and people of the camp."

In a café in nearby Tulkarm, Nehaya speaks to the BBC about her family's panicked flight, as Israeli troops stormed into the camp in early February.

For two days Nehaya watched and listened in terror as military bulldozers razed the area around her house.

"We were besieged inside our house and couldn't leave," she recalls, describing how power, water and internet connections were all severed.

Eventually, on 9 February, Nehaya escaped with her 75-year-old husband, Zaydan, and their teenage daughter Salma.

"When we got out, I was shocked by the damage in the area," she says.

The Israeli military launched "Operation Iron Wall" in late January, sending troops and armour into Nur Shams and two other refugee camps in the northern West Bank, to tackle Palestinian armed groups it said were responsible for attacks on Israeli soldiers and Jewish settlers.

The operation followed a largely unsuccessful attempt by the Palestinian Authority to quell the activities of local gunmen, many of them affiliated with Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad, in the parts of the West Bank where it governs and controls security.

By the end of February, the three camps had been all but emptied in the largest displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank since Israel occupied the territory in the 1967 Six Day War.

In Jenin, where the largest of the three camps dominates the western side of the city, we hear similar stories of terrified flight and long months of dislocation.

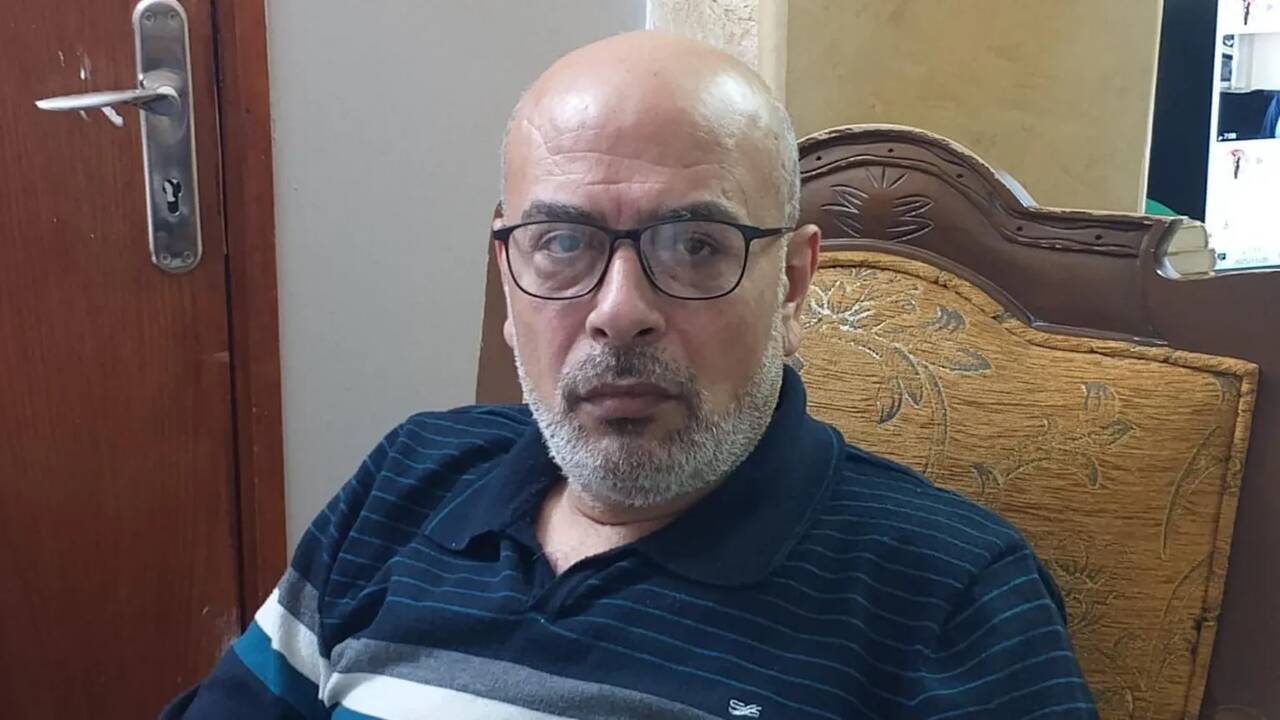

"We stayed three days in the house without power or water," says 54-year-old Nidal Abu Nase, a development consultant and freelance book editor.

"The shooting never stopped."

When the chance to escape finally arrived, Nidal's family left with little more than their clothes, thinking they would soon be back.

"I never managed to get home to collect my stuff," he says.

Ten months on, Nidal and at least 32,000 residents of the three camps still don't know when they will be allowed to return to their homes.

When that moment finally comes, many will find they no longer have homes to go back to.

Human Rights Watch says Israel has demolished 850 homes and other buildings across all three camps.

Other estimates rate the extent of the damage much higher.

In a report published earlier this week, HRW said Israel's forced, prolonged evacuations and the associated destruction "amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity".

"The Geneva Conventions prohibit displacement of civilians from occupied territory except temporarily for imperative military reasons or the population's security," HRW said.

The group said Israel's actions "may also be considered 'ethnic cleansing'".

In February, Israel's Defence Minister, Israel Katz, said he had instructed the army "to prepare form a prolonged stay in the camps that have been cleared for the coming year".

As the year's end approaches, there's still no end in sight.

An Israel Defense Forces spokesperson told the BBC that "in order to locate and uproot the terrorist infrastructure at its source, the IDF has had to operate for an extended period of time."

But already in August, Katz called the operation a success, saying "there is no terror in the camps and the scope of terror alerts in [the West Bank] has dropped by 80%."

The IDF says it has dismantled bomb-making and other weapons facilities hidden inside all three camps.

It is not clear why Operation Iron Wall continues, although demolitions are still happening in the camps.

It seems clear from the pattern of destruction and the Israeli military's own explanations, that the operation has longer term goals.

In a statement to the BBC, the IDF said armed groups had been able to exploit the densely built environment of the camps, making it hard for the army to move freely.

"The IDF is acting to reshape and stabilise the area," the IDF spokesperson said. "An inseparable part of this effort is the opening of new access routes inside the camps, which requires the demolition of rows of buildings."

Satellite images from all three camps show the extent of the damage, with narrow, barely visible streets now wide enough for military vehicles, including tanks, to pass through.

The demolitions, the IDF spokesperson said, were "based on operational necessity", with residents able to submit objections and petitions to Israel's Supreme Court.

All such petitions - some of which argued that Israel's actions violated international humanitarian law - have been rejected.

According to HRW, Israel's military has been given "wide discretion to invoke the grounds of urgent military necessity".

HRW has called on the Israeli military to halt the forcible displacement of Palestinian civilians throughout occupied Palestinian territory, and allow all the residents of Jenin, Tulkarm and Nur Shams to return to their homes.

For tens of thousands of displaced people, the future remains uncertain.

Nehaya al-Jundi's family eventually found refuge in a nearby village. But with their lives turned upside down and most of their possessions now out of reach, back in the camp, it's been a hard year.

"Everything has been difficult since we left," she says.

Nur Shams' tight-knit community has been scattered across the Tulkarm area. Some are living with relatives, others in rented accommodation.

Many are out of work, dependent on modest handouts from the cash-strapped Palestinian Authority and various NGOs.

With schools run by the UN agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) also out of action in the camps, education has also been severely impacted.

"My kids were enrolled in UNRWA schools," says Nidal Abu Nase, whose family has been living with relatives since January.

"They went for months without school."

Crucially, the camps' strong communal bonds have been fractured.

The residents of West Bank refugee camps are mostly descended from Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes during the war surrounding Israel's creation in 1948-49.

"For me, the camp is identity and culture," Nidal says.

"There was love and affection in the camp," Nehaya says, "but not anymore because we are far from each other."

Nehaya has not seen her house since February. Despite recent protests, very few residents have been allowed back into the camps.

The community centre where she ran rehabilitation services for the disabled has been turned into an Israeli military barracks.

And reports from young men who have managed to sneak into Nur Shams suggest that Nehaya's house is no longer habitable.

"They told me the house is wide open - and fully destroyed."

Additional reporting by Alaa Badarneh