Tintin in America: From Tommy Guns to Cowboy Hats

Medium | 27.12.2025 01:32

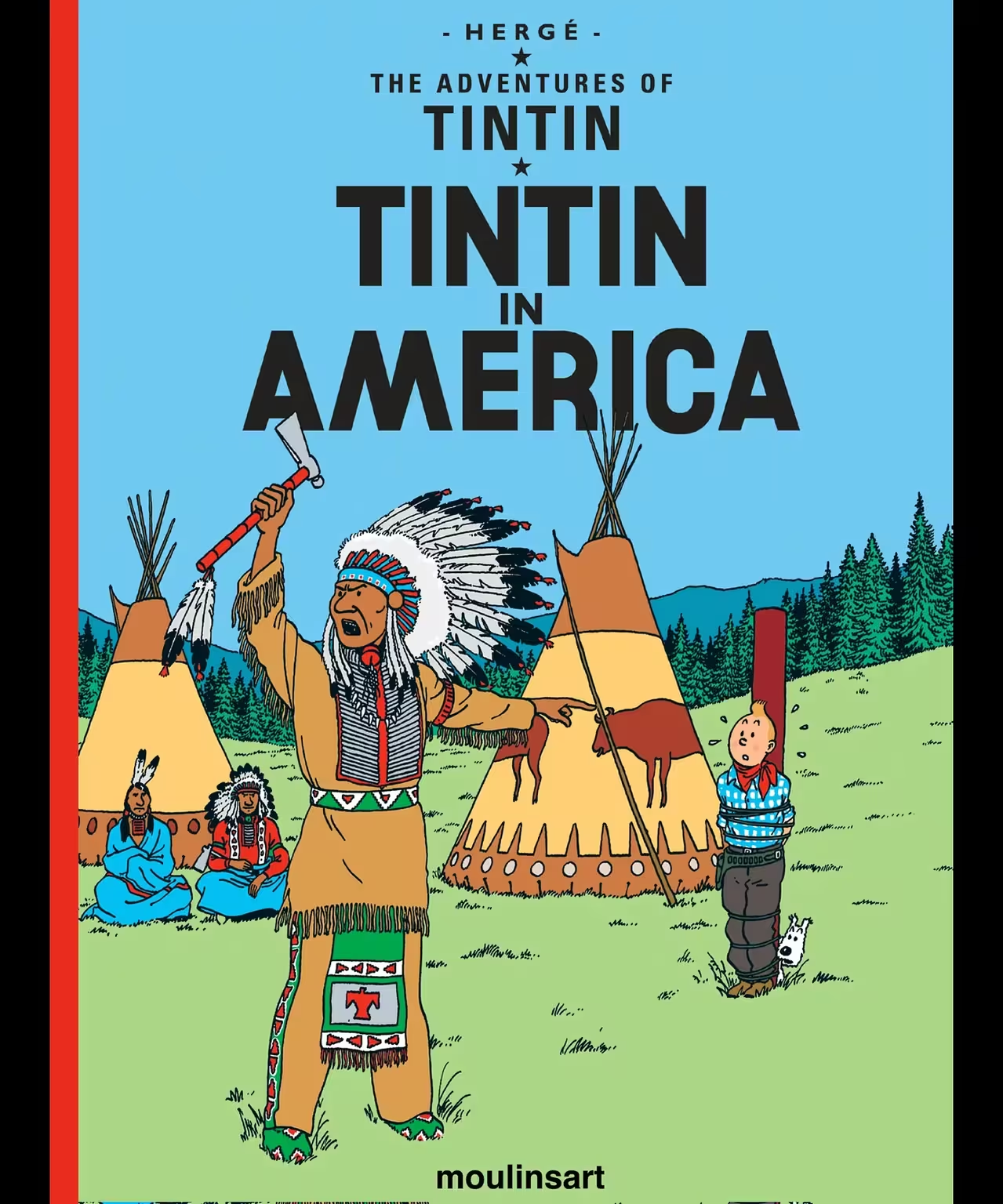

Tintin in America: From Tommy Guns to Cowboy Hats

As an American reading Tintin in America, I often find myself thinking, wait… what country does this book even take place in?

Tintin has visited countless cultures and met all kinds of people throughout his famous book series. But early in his career, he didn’t just visit America—he fought real-life gangsters like Al Capone. In only his third story, Tintin avoids drowning, gets shot at, wears a cowboy hat, is captured more times than I can count, and somehow finds himself switching between a sharp suit and full armor. I wish I could tell you this all happens across four different books, or that it somehow works as one cohesive adventure—but it doesn’t. Tintin in America is a mess. Not bad enough to hate, but definitely not good enough to love.

After Hergé’s controversial Tintin in the Congo, he followed it up with what many readers consider the true beginning of the Tintin franchise. I can only speak from my own experience: I’ve read every Tintin story multiple times, starting with Land of the Soviets and finishing with Tintin and the Picaros. And for those already asking—yes, I’ve read Alph-Art. I read it once. It’s hard to revisit because it isn’t really a story; it’s unfinished, and I don’t feel the need to return to it.

But back to Tintin in America. Every time I reach this third book, it feels like a hurdle—something I have to get through to reach the stories I truly love. It feels more like a chore than an adventure. Not because it’s terrible, but because it’s overcrowded and driven almost entirely by coincidence. I wish it were better. It’s frustrating in a different way than Congo—not bad enough to openly condemn, yet flawed enough that its weaknesses are impossible to ignore.

That said, glass half-full—there is a lot to like here. The idea of Tintin versus gangsters is simply a fun concept. Dodging gunfire, outsmarting mobsters, throwing fists when necessary, and even a full-blown train chase—Tintin vs. the mob is exactly what this story should have focused on.

I also love the cowboy look: the hat, red bandana, blue shirt, and revolver at his side. It feels classic and effortlessly cool. And yes—of course I own that figure. The pages of Tintin riding horseback through the West with Snowy at his side are genuinely great, and this story also marks the debut of Tintin’s yellow polo and brown slacks, which remains my favorite Tintin look to this day.

Even though the disguises are overdone—like a steak at a bad restaurant—they’re still fun. Each one feels like a small discovery, almost like scanning a Where’s Waldo? page just to see what Tintin is dressed as now.

On the opposite side of that coin are the elements that keep this story from being a classic. Al Capone, on paper, is a great villain choice. But using a real-life, controversial figure ultimately creates limitations. If Hergé had created a fictional gangster instead, we could have gotten a proper face-off—Tintin versus the boss, fists flying, and a far more satisfying conclusion.

And let’s be honest: the story is a mess. We’re in the city, then the West almost immediately, underground, back to the city, followed by two major train sequences. It wants to be everything all at once without giving the reader any time to settle in or enjoy the adventure. And don’t even get me started on some of the depictions of Native Americans.

Finally, if Tintin gets saved by one more coincidence, I’m going to start believing the theory that Snowy is his guardian angel. They give him the wrong gas. Water conveniently wakes him up. Come on—I’m rolling my entire body at this point.

As an American, I feel it’s necessary to address how this book represents the United States. One thing my dad has always said—and something I’ve come to really appreciate—is that while North America includes many countries, when people say “Americans,” they’re usually talking about the fifty states. And although I love Tintin and believe he belongs in this world, I don’t think this book does a great job of capturing what makes our country special or unique.

To me, what best represents the United States is its role as a melting pot—different cultures, beliefs, backgrounds, and ideas all existing under one shared umbrella. When I look at my coworkers, family, and friends, I see people of different nationalities, appearances, beliefs, and life experiences. Tintin in America, however, leans heavily on early depictions of Native Americans, gangsters, and the Old West, and that narrow focus feels like a disservice to the broader identity of the country.

I understand the historical context—it was written in the early 1930s, when ideas of America were far more limited. But revisiting it as a kid of the 1990s, it doesn’t feel like a story that truly represents my country. That said, it remains a timepiece, and one I can still appreciate. And yes—I proudly own this book.

That’s ultimately my point: Tintin in America has great moments and some not-so-great ones. I can’t call it one of the bad Tintin stories—and I believe there are two that truly earn that label—but this isn’t one of them. Compared to the greats, it’s not even close. Compared to the good stories, it doesn’t belong in the conversation. And compared to the “okay” books, I can’t honestly place it there either.

It’s better than bad, but definitely not good. It’s far from okay, yet it doesn’t hurt to read. In the end, it’s a Tintin story that simply… exists.

To wrap this up with a bow—is it worth reading? Of course. It does feel like early groundwork for the adventures Tintin would eventually grow into. Just know that it’s a rough start, and the story that follows, Cigars of the Pharaoh, is a thousand times better. I wouldn’t recommend skipping it outright, but it’s also not the Tintin story you’ll be excited to revisit.

Disclaimer: I am not saying that this isn’t a good Tintin book—and if it’s one of your favorites, I’m genuinely happy for you. For me, it’s simply a story I can take or leave. I always read it when I go through the collection, but that’s not saying much, since I read every book from Land of the Soviets straight through the entire series.

This is purely my opinion, and if this is a story you love, more power to you. That’s one of the best parts of being a Tintin fan—each story can hit differently depending on the reader. I hope you enjoyed this piece, and stay tuned for more random Tintin articles in the future.

All images used in this article are presented for commentary, criticism, and educational purposes under fair use.