Please Explain

Medium | 26.12.2025 22:37

Please Explain

Follow

8 min read

·

Just now

Listen

Share

It sounds open. It sounds fair. Yet every time it is spoken, the burden of proof slides back to the person who gave it. How does the bureaucracy of empathy keep helping busy instead of being useful?

“Please explain.”

Not every failure arrives as a refusal. Some arrive as an invitation that never ends.

You know the kind.

A phone call that begins with thank you for waiting and ends with please hold while we review your case. A letter that recognises the need, confirms the facts, appreciates your time, and asks for the same documents again.

No one slams a door.

The door is held open.

You are asked, kindly and repeatedly, to keep walking through it.

This is how help can fail: not by denying, but by continuing.

Families of disabled children learn the rhythm early. An application. An assessment. A promise. A delay. A request for updated evidence. A new person assigned to the file who needs to hear the story from the beginning. Each step looks reasonable on its own. Together they form a circle.

You move, but you do not arrive.

The circle is polite. That matters. It is easier to describe cruelty than kindness that exhausts you. Different waiting rooms with different chairs.

You are still here months later.

Forms grow familiar. You know which boxes demand long answers and which ones punish them. You keep a folder, then a drawer, then a hard drive.

Every retelling has a cost. To be believed, you must present the worst days again. You must describe the panic, the shutdown, the injury, the loss. You must choose words that land hard enough to unlock help without reducing your child to those words.

It is a craft you never wanted and a fluency you would trade for silence. You learn to write as if love were evidence.

Meanwhile, life happens in the margins of process. School starts without the support that was agreed upon in the meeting. A piece of equipment arrives after a growth spurt. By the time a decision reaches you, the facts on the page are true but already out of date.

Families notice something else too. The soundtrack. “We appreciate your patience,” “We’re doing all we can,” “We’re just waiting on another department,” “Unfortunately the assessment has expired; we’ll need a fresh one.”

Each sentence is understandable. Together they add up to a year.

Sometimes there is a win. A hearing goes your way. A letter arrives with the words you hoped to see. People congratulate you. Then you discover that a win is another starting line. A victory produces new correspondence, new waiting, new circles. You fight for the thing; then you fight for the thing to show up.

It would be simpler if there were villains. Mostly there are people. Teachers are watching classrooms and inboxes while caseworkers and therapists carry workloads no one can finish.

Many of them want the same change. Many of them would rather deliver than apologise.

They are not the problem. The arrangement is.

When help is arranged as a performance, families become performers. There is a script to learn: phrases like “impact on daily living,” “significant impairment,” “ongoing need.” There are cues to hit: bring a diary, keep a log, record the frequency. There is a stage: a panel, a desk, a screen. There is applause: thank you for your candour. And then there is the moment after the curtain falls, when you return to the same house and the same absence.

Not every failure announces itself. Some arrive wrapped in empathy, padded with process. Some keep you in the room so long you forget there is a door.

Children learn quickly.

They watch their parents become translators, advocates and clerks. They can tell when a meeting actually changed something other than the calendar.

None of this is unique to one country. The pattern is recognisable anywhere people must prove the obvious more than once. Different logos, same delay; different letterheads, same lost hour.

What does it do to a family to live this way?

First, it steals time. The minutes taken from care itself. From bath times, mealtimes and the bedtime you would have had if the meeting had not run over. The tasks of process risk replacing the tasks of living.

Second, it shapes memory. Ask any parent caught in this cycle to tell you about the last year and watch how their mind reaches first for dates and documents. The days are filed by case numbers/decision letters/reviews.

The joke that landed at the worst possible time and saved the evening, the moment a new skill arrived without warning – the ordinary memories – get pressed between pages of paperwork. They survive, but they are creased.

Third, it trains speech. You learn to talk about your child in the grammar of need. You can switch it off at home, but the switch sticks sometimes.

Get Ken O’Brien’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Over time, the circle hardens into a loop. It is no longer drawn by people but written into procedure itself.

Because the loop is polite, families often question their own impatience.

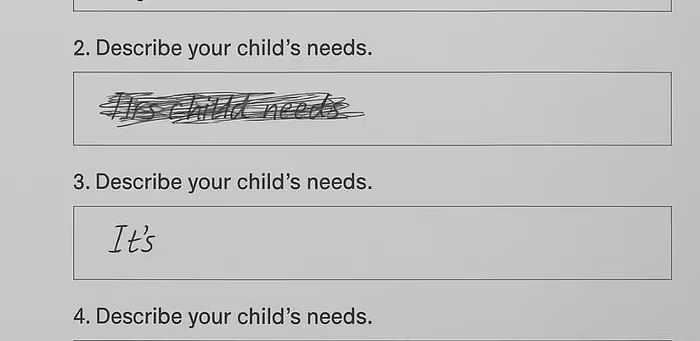

Maybe one more summary will help them help us. You think this until you realise you are writing the same paragraph for the fourth time, changing the wording so it looks new when it isn’t.

You stop and see the outline of the circle at last.

There are ways to break a circle that do not require blame. One is the principle of ask once. If a fact has been established by a decent process, it should stand. No annual re-injury of the story. Update what genuinely changes.

Another is the principle of time that counts. If a decision is made, a clock should start that belongs to the family, not the office. A plan that is late is not a plan; it is a promise that missed its moment.

There is a third: continuity that travels. When children move between settings or cross the artificial lines between stages of life, support should travel with them unless something better is ready in the new place. No gaps created by birthdays. No punishment for growing older.

Professionals know these things. Many try to live by them even when the procedure does not. They sneak continuity into their practice the way people sneak food into a hospital ward that doesn’t serve enough.

They say, “I’ll hold this, so you don’t have to repeat it.” They call ahead to the next team and explain what the file cannot. They do what they can. The tragedy is that kindness cannot scale when the design insists on repetition.

And because the design insists, families learn to conserve. You cannot bring your whole anger to every meeting, so you ration. You let minor errors slide to preserve strength for the major ones. You choose which late arrival to chase and which “we’re unable to locate that in the system” to swallow.

Every act of grace costs you something, and you pay it because the price of fighting everything is collapse.

Families known for being “persistent” are treated with a mix of respect and caution. Being firm risks getting marked as difficult. Being soft risks getting ignored. You try to be exactly the right amount of urgent and discover that there is no right amount.

All of this is avoidable in theory and stubborn in practice. The reasons are ordinary: budgets planned to the bone, staffing that never caught up, rules meant to prevent error applied to cases where the error is already obvious.

The loop doesn’t continue because it is evil. It continues because stopping requires discretion and trust. Trust is the one resource no process or institution can produce on demand.

Stopping would look like a call that ends with a date, not a promise. Like a letter that carries the change, not the thanks.

A meeting where the most important sentence is, “We have enough.”

Stopping would also look like rooms where parents aren’t asked to rehearse pain to keep support alive. Hours reserved for being with the child instead of describing the child. Weeks without a review. Months where the main task is not endurance but ordinary life – the sofa at the end of the day where no one is writing anything for anyone.

There is always a fear that stopping means neglect. It doesn’t. Stopping does not mean withdrawing care. It means honouring what has already been said. It means taking responsibility for the next step instead of creating another step for someone else to take.

It also means designing for rest. Families need the right to be boring for a while. To go weeks without a call about process. To live in the benefits of a decision instead of in the explanation of it.

Rest is not a luxury after help; it is part of what help is for. If help cannot make room for rest, it is not help yet.

There will be people who think this is naïve. That if you stop checking, misuse will follow. That if you stop asking, standards will fall. If you stop looping, something important will be missed.

Those people are right to care about care. They are wrong about the method.

Endless proof does not produce safety; it produces fatigue. And fatigue is where mistakes hide.

There is another worry: that talking this way shames the people doing the work. It shouldn’t. If anything, it points to what many of them already know and dislike.

No one goes into a caring role to become a choreographer of circles. Most would rather deliver one concrete change than send five perfect emails. Saying the loop is the problem is not an accusation against the people trapped in it with us. It is an invitation to step out together.

Let there be a clear line where a family moves from proving to receiving. Let there be an end to the part where they must keep showing the wound, so the dressing does not get removed. An end to the phrase “we’re nearly there” as a permanent address.

If you recognise yourself in any of this, know that you are not imagining it and you are not alone.

The point is not to become bitter. The point is to insist, gently and repeatedly, on endings that honour beginnings. On help that finishes what it starts.

The measure of care is not how many times a family was thanked for their patience. It is how many hours they got back.

The measure of fairness is not how carefully a story was heard. It is how quickly the hearing turned into doing.

The measure of respect is not how often a door was held open. It is whether you were allowed to walk through it once.

Families do not need another round of acknowledgement. They need decisions that turn into days, not delays. They need a season where the phone is quiet because the work is done.

They need help that knows when to safely let go.

People deserve more than to be held in place by the very hands that promised to move them forward.

Because help that never stops asking for an explanation is not help. It is how care forgets what it is actually for.