India’s Favourite Joke — The Tawaif

Medium | 08.01.2026 14:30

India’s Favourite Joke — The Tawaif

Follow

4 min read

·

1 hour ago

Listen

Share

In Bhabhi Ji Ghar Par Hain, laughter is manufactured cheaply.

One of its most reliable devices is Gulfam Kali—the bar dancer whose exaggerated mujras, suggestive gestures, and comic villainy invite viewers to laugh at her presence rather than think about what she represents. On the surface, she is harmless entertainment. Beneath it, however, lies a familiar and troubling pattern: the tawaif reduced to a moral punchline.

This is not merely about one character in one sitcom. It is about how popular Indian television continues to recycle a degraded image of hereditary performers—stripped of history, flattened into stereotype, and presented as culturally inferior to the “respectable” domestic world the show celebrates. Gulfam Kali is not named a tawaif, but her visual grammar is unmistakable: the kotha, the mujra, the excess, the implied availability.

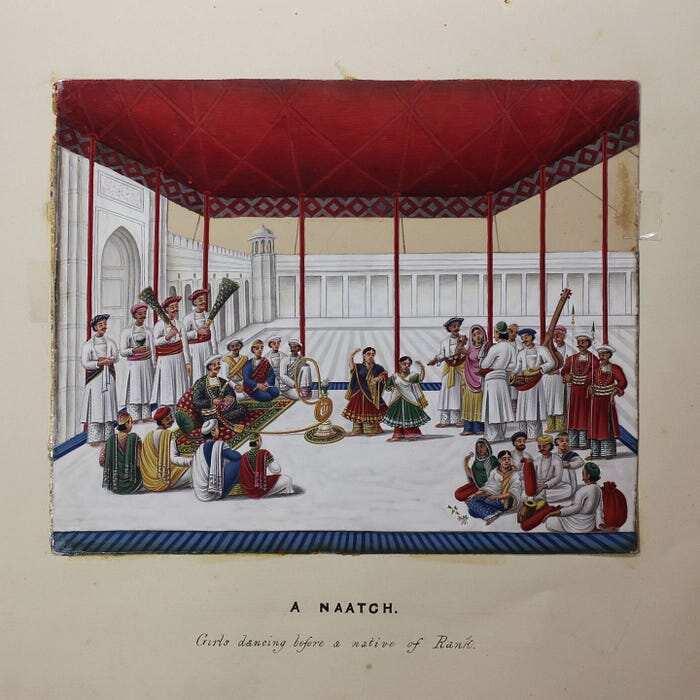

What is being mocked is not just a fictional woman, but an entire lineage of cultural labour. Historically, the tawaif was not a marginal figure. She was central to the development of Hindustani music, Urdu poetry, courtly etiquette, and aesthetic pedagogy.

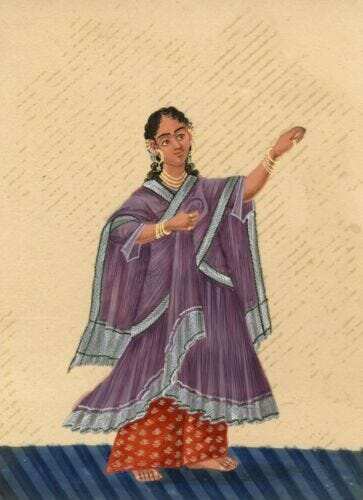

Tawaifs trained elite men in language, taste, and comportment; they sustained sophisticated systems of artistic transmission long before formal conservatories existed. Their worlds were governed by discipline, lineage, and rigorous training—not by the cheap eroticism with which contemporary media insists on associating them.

Television, however, has inherited a colonial and postcolonial moral script that cannot accommodate such complexity. The mujra, once a refined performance practice, is now coded as inherently vulgar. The kotha, once a space of cultural exchange, becomes shorthand for moral decay.

Gulfam Kali’s performance is never allowed dignity or interiority; it exists only as spectacle, something to be laughed at, feared, or morally dismissed. This flattening is deliberate. Sitcoms thrive on binary morality: the good wife versus the bad woman, domestic virtue versus public excess.

Get Nirav Sachan’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

In this schema, the tawaif-like figure must remain perpetually outside respectability. She cannot be intelligent without being manipulative, talented without being dangerous, or expressive without being obscene. The joke depends on her remaining illegible as a full human being. What makes this portrayal particularly insidious is its claim to innocence.

Comedy, after all, is “just comedy.” But popular culture does not merely reflect social attitudes—it reproduces them.

When mujra is repeatedly framed as laughable, when dancers are depicted as predatory or ridiculous, audiences absorb a lesson about whose labour counts as culture and whose counts as contamination. The result is not harmless humour, but cultural amnesia. This amnesia has consequences. Hereditary performers across India have spent decades battling stigma created by precisely these narratives.

While their histories are erased from textbooks and institutions, television resurrects them only as caricature. The same society that once criminalised, reformed, and abandoned these communities now consumes their distorted images as entertainment. Gulfam Kali is not offensive because she dances. She is offensive because the show cannot imagine a dancer without moral degradation.

Her body is allowed visibility, but not history. Her performance is shown, but never respected. This is not accidental—it is how cultural hierarchies sustain themselves. If Indian television wishes to be more than noise, it must learn to treat cultural memory with responsibility. Comedy need not be reverent, but it must be conscious.

The tawaif does not need romanticisation, but she does deserve historical honesty. Until popular media learns the difference, it will continue to laugh at what it has already helped erase.

And some jokes, especially those built on centuries of silencing, are simply not funny anymore.