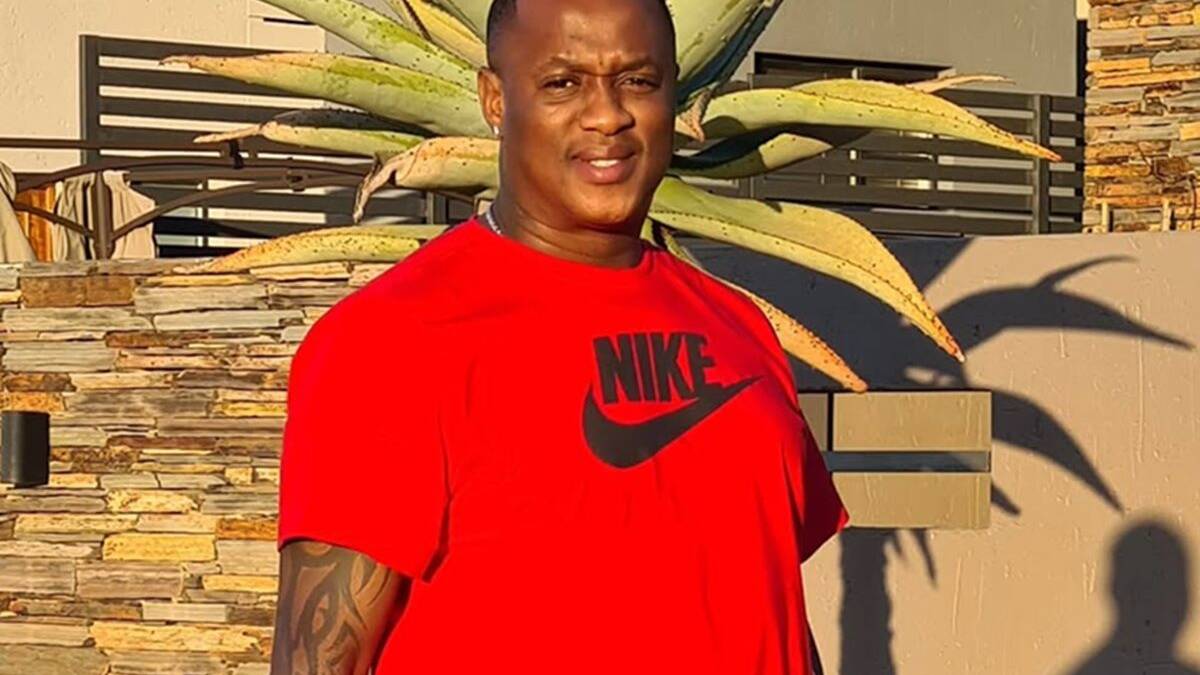

Interview With Zonja Penzhorn, founder and CEO of Human Nature Africa

StartUp Magazine | 09.02.2026 16:48

Interview With Zonja Penzhorn, founder and CEO of Human Nature Africa. Human Nature Africa founder and CEO Zonja Penzhorn has built her work at the intersection of lived experience, social innovation, and prevention-focused mental health support. In this interview, she reflects on the personal health crisis that reshaped her understanding of care, the role nature played in her recovery, and how those insights led to the creation of Plant Play, a gentle, child-led programme designed to support emotional expression without labels or stigma. Through her responses, Penzhorn unpacks the thinking behind using a single flower as a tool for growth, the lessons learned from piloting the programme in Diepsloot, and why early, preventive investment in children’s emotional wellbeing is critical for South Africa’s long-term social and economic stability. Read about it below!

What inspired the idea behind Plant Play, and why did you choose a flower as the centre of the programme rather than a more traditional intervention tool?

I remember waking up on the morning of my first physical “attack”. I was getting ready to do a live webinar. I got dressed, looked in the mirror, and my right eye started pulling outward and the corners of my mouth started pulling. It was all uncontrollable.

I remember thinking: this is it. I’m having a stroke or a heart attack. Something I had been expecting for over a year. It was now happening.

I nearly fell to the floor but held onto the sink. My knees buckled. It lasted about 30 seconds, but it felt like hours. The only thing I could think about was that I didn’t want my mom to have to find me or have to look after me. That was my job.

I managed to pull myself out of it and went on to do the webinar. I looked terrible and I was exhausted, but the presentation was one I had done many times before, so it was second nature.

The next day, during a meeting, I had another attack. I called my mom to take my blood pressure. It was 180 over 113. I had an emergency appointment with the doctor.

The fibromyalgia diagnosis was only confirmed later, in November. This was May.

During this time, I was extremely sick and we were trying to find out what was wrong with me. I was booked off for an extended period due to my symptoms. These were early days and the first signs that something serious was happening.

I was in Hoedspruit, sitting on the deck overlooking the bush. I felt extremely grateful and privileged to be able to be in nature. Being there brought me a sense of calm and peace that I couldn’t find anywhere else.

That’s when I started thinking: I wish everyone could experience this. I thought about how people have to work continuously just to make ends meet. I thought about people living in cities and asked myself where they ever step into nature, or how they find peace.

That’s when the idea formed: what if nature could be the support people need, emotionally and financially? There are things in nature that need fixing, and there are people who need help. Bringing those together could give people purpose. You can see progress. You can see growth. You can see potential. Nature shows us how we can rise from our circumstances.

At the same time, I was already very aware of the support being provided in the social sector and how some terminology becomes a barrier. I was struggling to articulate what was wrong with me because I did not want to be labelled. I did not want to come across as weak or less than. And I work in this field.

So I kept thinking: if I don’t want to be labelled, how would a young child ever say how they are feeling? Why would they want to be associated with words that make them feel embarrassed or different, even if those words are meant to help them?

The doctor told me that at the time my symptoms were due to burnout, severe stress, exhaustion, and trauma. She put me on antidepressants and I immediately started crying. I said, I am not depressed. I am not weak. I already have so much anxiety from unacceptable and unrealistic pressure at work. How are they going to treat me now?

“Look after the land and the land will look after you.” That became the basis for Human Nature Africa.

I then thought about children. Through my work in gender-based violence, HIV prevention, and mental health, I knew the statistics and I knew how deeply children are impacted. Children cannot work. They cannot travel. They cannot remove themselves from their environments.

So the question became: how do we bring nature to them?

What if they could grow a flower?

That was the birth of Plant Play.

I did not want it to be tied to adult duties like food security or financial gain. I’ve worked in this field long enough to understand the pressure points. I wanted something gentle. Something that allows care and responsibility without fear.

The hyacinth bulb carries strong symbolism. Can you explain its significance and how children connected with it during the pilot?

The hyacinth was chosen very deliberately. First, for its beauty and fragrance, because we wanted the children’s experience to be sensory and positive from the start.

The hyacinth blooms mid-year, which aligned with the start and end of the school syllabus. This mattered so the programme could sit naturally within the school year and allow children to see a full growth cycle.

The bulb does not die. After blooming, it can be kept and bloom again each year with care. That mattered because it shows that growth does not end; it pauses and returns.

When a hyacinth bulb is cut open, the flower already exists inside it. Children understood that growth takes time, care, and patience, and that progress is not immediate.

Why was Diepsloot selected for the four-month pilot, and what were your biggest learnings from working in that environment?

Diepsloot was selected because it is one of South Africa’s highest gender-based violence areas, and because of my existing work across gender-based violence, HIV prevention, and youth mental health. It is an environment shaped by overcrowding, poverty, crime, and instability, where children are exposed to adult stress and responsibility far too early.

The intention was to pilot Plant Play in a place where pressure is constant, not occasional. If an intervention cannot work in an environment like that, it is unlikely to work anywhere else.

What became very clear, very quickly, is how desperate children are for conversation and connection when they are not being labelled or analysed. These children are carrying a lot — fear, anger, sadness, confusion — but they rarely have safe spaces where they can speak without consequences.

Once children felt safe, they spoke freely. They spoke to facilitators, to each other, and often through the plant itself. They supported one another naturally. The issue was never a lack of emotion or awareness. The issue was the absence of spaces that allow children to express what they are carrying in a way that feels safe and dignified.

From a startup and innovation perspective, how did you design Plant Play to support children’s emotional expression without creating barriers to communication?

Plant Play was shaped directly by my lived experience and my professional experience.

I was already very aware of how language and labels operate in the social sector. I knew that when people — especially children — feel defined by words that make them feel embarrassed, weak, or different, they often shut down. When children stop talking, adults lose the ability to understand what the child is going through and why. And when understanding is lost, access to meaningful support is lost as well.

Plant Play was designed to remove those barriers. It does not ask children to explain themselves upfront. It gives them an experience first.

Through caring for something living, children begin to express emotions in their own way and in their own time. Frustration, pride, disappointment, attachment, patience and loss all emerge naturally through the relationship with the plant. This allows adults to understand what a child is experiencing without forcing terminology that closes the conversation.

The focus is not on fixing a child. It is on helping children learn emotional regulation so they can cope with their circumstances, rather than being overwhelmed by them or acting them out.

Can you share more about the moment when a learner said she could not take her plant home, and how that influenced the programme’s direction?

Early in the programme, one learner said she could not take her plant home. When she was gently asked why, she explained that when her parents fight, they break things.

That moment mattered because it revealed how much children are managing silently, and how quickly they will speak when they feel safe. There was no drama, no disclosure process, no pressure. Just a simple statement that carried a lot of meaning.

It reinforced why Plant Play needs to remain gentle, flexible, and child-led. Not every child’s home is safe. Not every child can take responsibility in the same way. The programme needs to meet children where they are, rather than assuming what support should look like.

That moment also confirmed that children do not need to be pushed to talk. They need to be given permission.

What behavioural or emotional changes did you observe among the 265 learners throughout the project?

Over the course of the programme, children became more emotionally expressive and more emotionally regulated. Communication increased, both with peers and with adults. Emotional outbursts reduced, not because children were being controlled, but because they had an outlet.

Children took pride in caring for their plants. They checked on them daily. They spoke about them. They worried about them. They celebrated small changes.

We also saw a reduction in boredom-related risky behaviour. Having something to care for gave children a sense of responsibility and purpose. It anchored them. For many, it was the first time they had been trusted with something living.

Parents and teachers reported meaningful shifts in communication and confidence. Which outcomes stood out most to you as a founder?

What stood out most was not a single behaviour change, but a shift in how children related to themselves and others.

Parents reported that children were talking more openly at home. Teachers noticed increased confidence, participation, and focus, particularly among learners who had previously been withdrawn or disruptive.

The most important outcome was emotional safety. Children felt safe enough to speak, to try, and even to fail. That safety changes how a child shows up in every other area of life — learning, relationships, and decision-making.

How does Plant Play challenge traditional gender roles and encourage empathy among both boys and girls?

Plant Play does not assign roles based on gender. Care, responsibility, patience, and consistency are shared equally.

Boys were given permission to nurture and care without being judged. Girls were given permission to take responsibility and lead without being overburdened. Empathy emerged naturally through shared experience rather than instruction.

By working together around something living, children learned cooperation and mutual respect without being told what those concepts mean. They experienced them.

What role does collaboration between community, civil society, government, and the private sector play in scaling the initiative sustainably?

Community trust and civil society partnerships are essential for delivery. Without trusted local partners, you don’t reach children in a way that is safe, ethical, or meaningful. Government alignment matters because this work needs to support national priorities, not sit outside them.

South Africa’s National Development Plan is clear about its goals around social stability, education outcomes, employment, and safety — and we are behind on those targets. Many of the areas where we are struggling most are directly linked to children growing up without the emotional tools to cope with sustained pressure, fear, and instability.

This is where the private sector becomes critical. Corporate South Africa already invests heavily in CSI, but much of that funding still goes into responding once harm has already happened. Prevention requires a different mindset. It means investing earlier, before distress becomes behaviour and before social issues escalate.

It also makes smart business sense. These are the children who will become the future workforce and future consumers. If we don’t invest in their ability to cope, regulate, and participate meaningfully in society, the long-term costs will show up everywhere — in education systems, in unemployment, in violence and crime, and in reduced economic participation.

We also need to be honest about what children are currently being offered. We see an increase in child-focused products in prominent retailers — more things to play with. But having more things does not necessarily help a child learn how to cope with their environment.

For many of the children in Plant Play, this was the first time they had ever owned something of their own. It came with real responsibility, but without punishment. If they failed, no one was upset. That safety is important. It’s what made them want to try, and to try again.

The plant gave them confidence. It became a quiet right of passage — permission to care, to be trusted, and to step into themselves. That kind of experience can’t be bought off a shelf. It has to be created through intentional collaboration across sectors.

As you aim to expand Plant Play across South Africa’s highest GBV-ranking areas, what are the next strategic steps for growth and long-term impact?

South Africa spends approximately R12 billion each year on Corporate Social Investment. The issue is not whether funding exists — it’s how that funding is allocated. Too much is still directed at crisis response, and not enough at prevention.

Plant Play is a prevention intervention. With funding, the next step is to scale into South Africa’s 30 highest gender-based violence hotspot areas and reach at least 15 000 children early, before distress becomes behaviour.

If we don’t intervene early, the consequences are already clear. We see rising suicide rates among young people, persistent youth unemployment, gender-based violence, crime, and declining education outcomes. Mental health challenges sit underneath all of this — and when they’re not addressed early, they show up later as violence, abuse, disengagement, and instability.

South Africa is already behind on its National Development Plan 2030 goals. The cost of inaction is not abstract. These are the communities your children will live in. These are your future employees and your future customers.

The question for corporate South Africa is not whether we can afford to invest in prevention — it’s whether we can afford not to.