The Flood as Earthquake: Amos, Texas, and the Policy Choices That Decide Who Dies

Medium | 22.01.2026 05:37

The Flood as Earthquake: Amos, Texas, and the Policy Choices That Decide Who Dies

Gordon Michael Alexander Clark

4 min read

·

Just now

--

Listen

Share

The People’s Pulpit

Amos and the Logic of Disaster

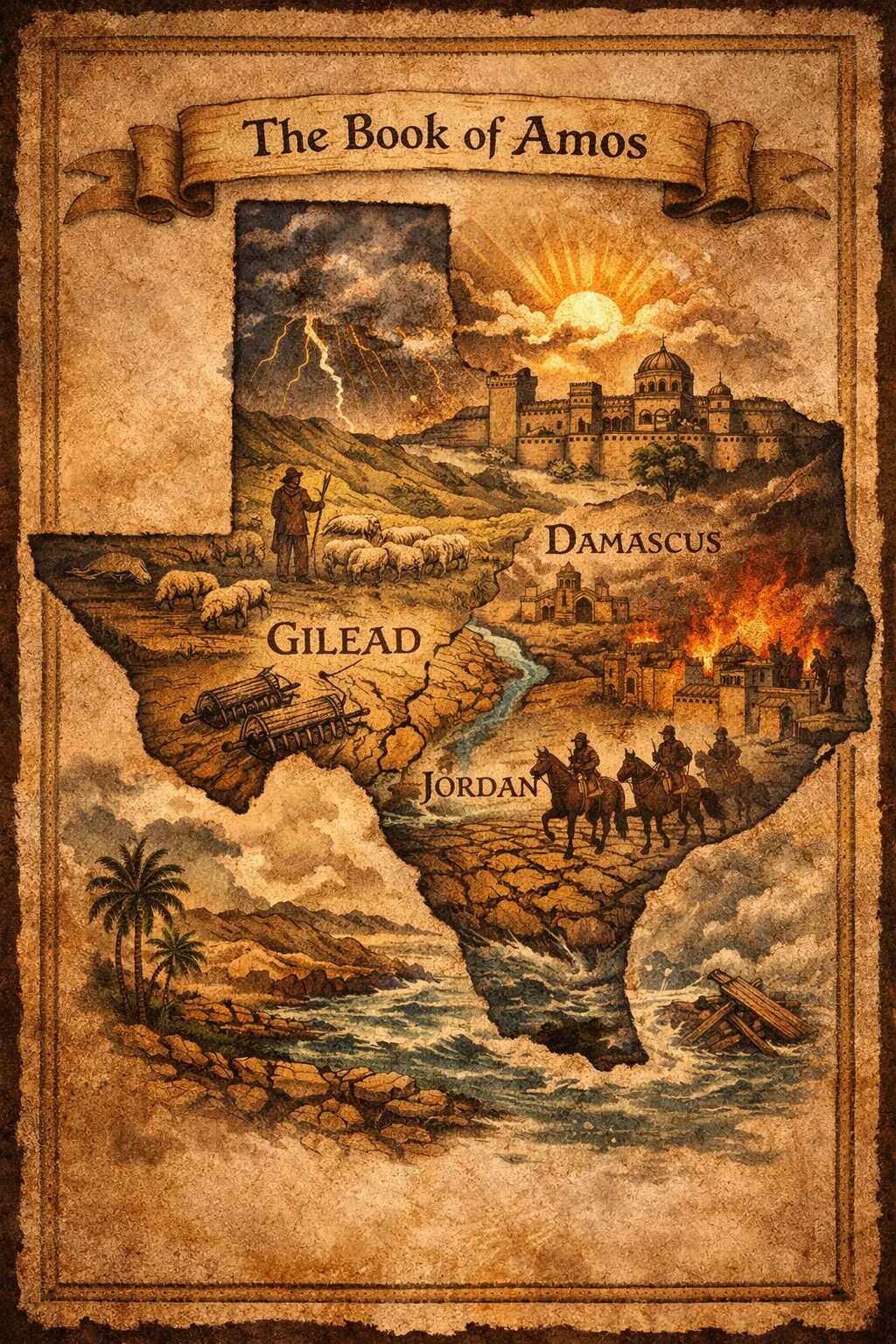

The book of Amos begins by dating prophecy in relation to catastrophe: “two years before the earthquake.” This is not an aesthetic flourish. It establishes a framework in which disasters function as moral disclosures rather than arbitrary interruptions. Warnings are issued before the ground gives way; history remembers the collapse, not the caution.

That structure matters for reading the recent floods in Texas. The event has been widely described as an unfortunate convergence of weather and geography. Yet climate science and disaster research point to a more precise conclusion: while rainfall initiates floods, policy determines mortality. Amos does not attribute disasters to divine caprice. He treats them as moments when social arrangements fail under pressure, revealing what had already been decided about prevention, preparedness, and whose lives are protected.

In Amos 1:2, “the LORD roars” and the land responds—pastures mourn, Carmel withers. The roar is not thunder; it is consequence. It is the sound a society hears when denial collapses. In Texas, that sound is not metaphorical. It is the accumulation of preventable loss—families displaced, systems overwhelmed, and children dead in places presumed safe. Reporting on the July 2025 Hill Country floods documented extraordinary rainfall interacting with terrain and infrastructure, producing rapid and deadly inundation . Climate agencies have been explicit that such extremes are foreseeable in a warming atmosphere that holds and releases more moisture, particularly when drought-hardened soils amplify runoff . Foreseeability converts tragedy into accountability.

Prevention Is Policy, Not Weather

Disaster specialists consistently show that mortality decreases where mitigation and preparedness are funded: floodplain management, resilient infrastructure, early warning systems, and community response capacity. These measures are politically vulnerable precisely because they prevent crises rather than dramatize them. In recent years, however, prevention has been reframed as ideological excess rather than material necessity.

The rise of a “government efficiency” frame—popularly branded as DOGE—has functioned as a reallocation of moral attention. Reporting documented DOGE-linked reductions affecting civic and service programs, including cuts to AmeriCorps grants that support disaster response and recovery capacity . Such decisions do not merely shrink budgets; they thin the connective tissue that allows communities to absorb shocks.

Amos’s critique targets these decision points. His “fire” falls on houses, gates, and strongholds—sites where priorities are set and resources controlled. When governments privilege culture-war signaling over climate preparedness, they redistribute risk downward. The flood does not ask about ideology; it follows physics. But physics interacts with policy. To know the risk and defund prevention is to participate in harm.

Vulnerability, Race, and the Geography of Harm

Disasters do not distribute evenly. They follow existing lines of vulnerability shaped by segregation, underinvestment, and political marginalization. Research on disaster recovery repeatedly finds that socially vulnerable communities—often defined by race, income, and housing precarity—receive less assistance and recover more slowly, even after controlling for damage . Studies in Social Forces document how institutional processes stratify recovery through appraisal and eligibility criteria that disadvantage high-minority communities , while policy analyses show that counties with higher shares of Black, Hispanic, or Native American residents often receive less FEMA assistance than mostly white counties with comparable losses .

Civil rights organizations have long connected these outcomes to structural racism in housing, infrastructure placement, and political representation . Amos’s condemnation of violence against Gilead—a borderland, easily sacrificed by empires—maps directly onto this reality. The prophet’s moral geography is not symbolic; it is diagnostic. If the same communities predictably bear the brunt of disaster, the problem is not nature but power.

This context clarifies the deaths of children during the Texas floods. Such losses collapse abstraction. They expose the distance between warnings and preparation, between rhetoric and protection. Amos never blames those on the ground. He indicts those at the gates—the institutions that normalized exposure by treating prevention as optional.

Accountability After the Roar

A credible theological reading of climate disaster avoids attributing storms to divine punishment while refusing moral evasion. Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’ articulated a widely cited framework linking ecological degradation with social injustice, insisting that the “cry of the earth” and the “cry of the poor” are inseparable . Scholars such as Willis Jenkins argue that climate change demands institutional responsibility grounded in real ecological pressures rather than abstract blame , while Catherine Keller cautions against apocalyptic language that obscures accountability instead of clarifying it . Racial theologians like Willie James Jennings emphasize how land, race, and power shape vulnerability, making climate justice inseparable from racial justice.

In practical terms, accountability after the flood requires more than mourning. It requires restoring and expanding mitigation funding, investing in early warning and resilient infrastructure, protecting community response capacity, and reforming disaster aid so it corrects rather than reproduces inequity. It also requires rejecting a politics that treats culture war as governance and neglect as virtue.

Amos’s closing pressure point remains decisive: once the earth has spoken, will the gates change? The flood functions as an earthquake only if exposure leads to reform. Rebuilding the same strongholds and calling the outcome “normal” ensures that the next roar is already forming—warm air over warm water, meeting systems that chose performance over protection.