Have You Tried…?

Medium | 07.01.2026 17:45

Have You Tried…?

6 min read

·

1 hour ago

--

Listen

Share

It sounds like curiosity. It often arrives wrapped in good intent. A professional leans forward slightly, pen poised, voice open.

“Have you tried…?”

The sentence feels reasonable. Collaborative, even. It suggests possibility. It implies that something small, overlooked, might unlock what has been stuck. The tone is rarely sharp. The words are rarely new.

The question appears most often at moments of visible strain. A child is struggling. A family has arrived at the edge of what they can manage. Something has not worked the way it was supposed to. The question steps in to soften the moment, to keep it moving, to fill the space where certainty has run out.

“Have you tried a visual schedule?”

“Have you tried reducing demands?”

“Have you tried a reward system?”

“Have you tried giving them more time?”

The suggestions are familiar. They are often correct in theory. Sometimes they are useful. Often, they are the very first things a family ever tried.

It is not an offensive statement. It is not meant to accuse. That is why it is so difficult to challenge.

Because what the question does is not obvious on the surface. It does not announce its assumptions. It carries them quietly, embedded in the grammar.

To ask have you tried is to imply that the thing being suggested is new, or at least untested. It suggests that the current difficulty might be explained by omission rather than constraint. That if the right strategy had been applied, the problem would not still be here.

It reframes struggle as unfinished effort.

The families hearing this question rarely respond with irritation. They have learned better. They understand the rules of the room. They know that frustration will be read as resistance, and resistance will stall the conversation.

Instead, they answer.

Sometimes they answer honestly. Yes, they tried it. It worked for a while. Then it stopped. Or it worked in one setting and failed in another. Or it worked until the child grew older, heavier, louder, more aware. Or it worked until the rest of life intervened.

Sometimes they answer selectively. Yes, they tried something like that. They do not mention the cost. The nights it took. The adjustments layered on top of adjustments. The way it required constant vigilance to maintain.

Sometimes they answer defensively, though they try not to sound that way. Yes, they’ve tried it – and several variations besides. They list them carefully, aware that too much detail can sound like challenge.

And sometimes they simply say yes, and move on, because correcting the assumption feels harder than carrying it.

What the question compresses is time.

Years of work are collapsed into a present-tense suggestion. Trial and error becomes a checkbox. Iteration disappears. The distance between we tried and we are still trying is erased.

What remains is a simplified version of the story, one that fits the moment but not the reality.

The question also flattens expertise.

The irony is that families are not asking for novelty. They are asking for accuracy. A strategy does not become more valid because it is spoken in professional language, and it does not become less valid because it was discovered at two in the morning by someone trying to keep a house from tipping. But rooms treat credibility as something that arrives with a lanyard. The same idea, carried by a parent, can sound like guesswork. Carried by a professional, it becomes “a plan.” The difference is not the strategy. It is who is allowed to sound certain.

In these conversations, knowledge is assumed to flow in one direction. The professional brings strategies. The family brings experience. The strategies are visible, named, credentialed. The experience is diffuse, unlabelled, difficult to summarise.

The question “have you tried?” places the professional as the holder of solutions and the family as the site of application. If something has not worked, the implication sits gently but firmly with the family. Perhaps the strategy was not applied consistently. Perhaps it was not done quite right. Perhaps it was abandoned too soon.

The possibility that the strategy itself might be insufficient – or incompatible with the child, the environment, or the reality of the family’s life – remains unspoken.

This is not because professionals are unwilling to consider complexity. It is because complexity is difficult to hold in a short exchange, and the question offers a way to move forward without sitting inside uncertainty.

The question keeps the interaction orderly.

There is a moment, rarely acknowledged, when the question lands.

A pause that lasts only a second or two.

In that pause, the parent decides who they need to be in order for the conversation to continue.

They weigh their options quickly. If they say no, they risk sounding unprepared. If they say yes and explain, they risk sounding defensive. If they list everything they have already tried, they risk being seen as difficult or overwhelming. If they keep it brief, they risk being misunderstood.

This calculation happens silently. It is not rehearsed. It has been learned over time.

In one room a parent answers too quickly. “Yes.”

The professional smiles, relieved. “Great – keep going with that.”

The parent doesn’t correct the relief. They don’t say that the visual schedule worked only when the day was quiet, only when sleep had been decent, only when the timetable stayed stable long enough to be believed. They don’t say it failed the moment the school day began adding surprises.

They let the conversation move on, because explaining the failure would take more time than the room has.

By the time the answer is given, it has already been edited.

What is left out of the answer is often as important as what remains. The failed attempts. The partial successes. The strategies that worked only at home, or only on good days, or only when nothing else was happening. The exhaustion that comes from holding a system together long enough to see whether something might help.

None of that fits neatly into the question as asked.

“Have you tried…?” is not designed to hold the answer it invites.

The question also performs another function. It protects.

It allows the professional to remain helpful even when resources are limited. To offer something when there is nothing else to give. To keep the interaction constructive without promising change.

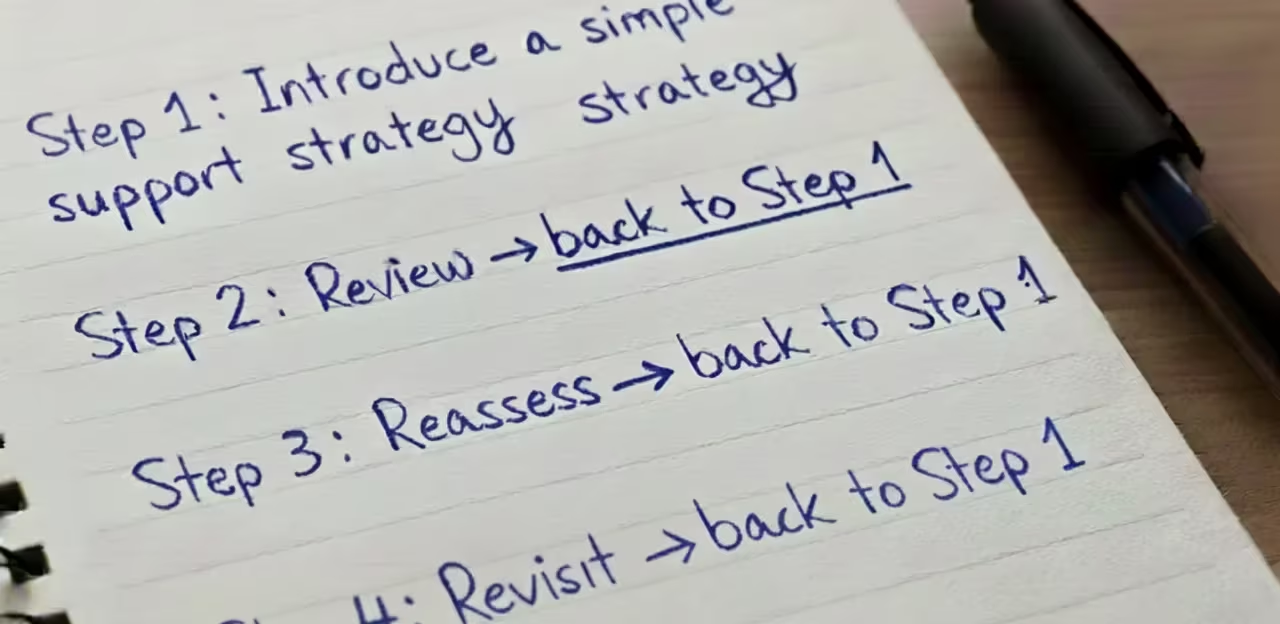

In this way, the question becomes a kind of conversational scaffolding. It keeps authority intact. It keeps the system competent, even when it cannot be effective.

No one has to say: we don’t have anything more to offer. No one has to name the limits of provision. No one has to acknowledge that the problem might not be solvable within the available structures.

The suggestion fills the gap where action would otherwise need to be.

Over time, families learn the pattern.

They begin to anticipate the question before it is asked. They arrive prepared with evidence of effort. They adjust their language to pre-empt assumptions. They stop mentioning strategies that failed, because failure invites repetition.

Some stop asking certain professionals altogether. Not out of resentment, but out of efficiency. The conversation has become predictable, and predictability is something they manage carefully.

This is not withdrawal. It is adaptation.

The question teaches families something quietly: that expertise must be performed in a particular way to be recognised. That lived knowledge is provisional unless confirmed by a professional source. That effort is assumed absent unless proven otherwise.

None of this is intentional. That is what gives the question its staying power.

“Have you tried…?” sounds like help. It feels like help. It is often offered by people who genuinely want things to improve. But it carries a subtle reordering of authority that leaves families doing more work than is visible.

There are other ways to ask.

Questions that move expertise both ways. Questions that assume effort rather than test for it.

Questions that make space for what has already been learned, even when it didn’t lead to resolution.

“What have you already tried that didn’t hold?”

“What works at home but falls apart here?”

“Where does it get hardest?”

These questions do not promise solutions. They do not tidy the moment. They do something quieter.

They recognise that the family has been working long before this conversation began.

When that recognition is absent, families adapt again. They shorten their answers. They withhold context. They protect themselves from being misread.

Eventually, the question stops landing as curiosity at all. It becomes a signal.

Not of help, but of how much explanation will be required before anything changes.

And sometimes, of how unlikely that change is to come.

The sentence remains polite.

The tone remains calm.

The conversation moves on.

What is lost is not goodwill, but trust – the particular kind that allows people to speak freely without first calculating how they will be heard.

“Have you tried…?” does not silence families outright.

It teaches them when silence becomes safer.