A morning, A kitchen and Inherited Masculinity

Medium | 26.12.2025 19:17

A morning, A kitchen and Inherited Masculinity

Follow

4 min read

·

1 hour ago

Listen

Share

- When equality feels like defiance

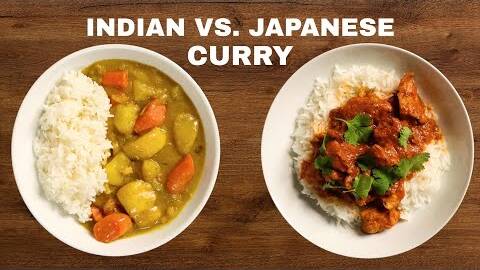

I woke up to voices echoing from every corner of the house, my father, grandmother and aunt, each shouting about a different problem. One worried that the havan kund wasn’t ready yet, another complained that the house wasn’t clean enough. Someone else fretted that the curry seemed different from usual and all of them equally pissed about me still being asleep. It was the day of my grandfather’s annual rites, and calm seemed impossible. My father was especially on edge, more than usual, knowing he had to leave for another state immediately after the rituals.

Soon enough, it was three o’clock. My father had left, I had more or less forced my patti to take a nap, and the entire house was in disarray. There was a mountain of utensils to wash, floors to sweep, rooms to clean, endless work, it seemed. We were short of two people: my father and my other aunt. That left just the two of us.

Then, unexpectedly, my uncle came home. And it seemed very natural to me that he joined the wagon. He took charge of the kitchen, washing and drying utensils. My aunt handled the rest, and I was assigned the smaller scut work.

The three of us talked as we worked, joking, vibing, singing, and before we knew it, everything was done. Soon, we were sitting around with coffee in hand, the house finally quiet. When my patti woke up a little later, she was confused about how all the work had finished so quickly. Her confusion turned into visible shock when she heard that her son-in-law had helped. Knowing I wouldn’t respond well to her shouting, especially about this, she turned to question my aunt instead. But the conversation came to an abrupt end when I launched into my rant about how men using a few muscles to help around the kitchen isn’t some terrible crime.

What unsettled me most wasn’t the reaction itself, but how instinctive it was. No one paused to ask whether the house felt lighter, or whether the day had ended more peacefully. The discomfort came solely from who had done the work. That was when I realised that what felt completely natural and right to me was considered wrong by a whole lot of people. It made me deeply curious, when and how were men taught this? How did they come to believe that this wasn’t masculinity, but domination was; that making women feel inferior, denying them respect, and treating kitchen work as something beneath them was the proper way to be “manly”?

My grandmother, who has been relentlessly working, never for herself and only for her family the past 60 years of her life,has only recently grown somewhat accustomed to my father doing household work, tasks that were traditionally meant to be done by women. She didn’t accept this wholeheartedly, she accepted it out of necessity, because there simply was no other option. Over time, routine softened resistance, not because beliefs had changed, but because life demanded adjustment.

Get Maanassa Raghunathan’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

A man stepping into a kitchen had disrupted an order that many had learned not to question. I don’t think these beliefs are born out of malice. They are inherited, passed down quietly through generations, reinforced by remarks and raised eyebrows. And perhaps that is why unlearning them feels so threatening. Because it demands reflection and not rebellion. Even when not sharing the workload places an extra burden on them, many women are taught to see this imbalance as a form of respect for the opposite sex. And when boys grow up witnessing this from a young age, it is, of course, bound to instill a sense of superiority. And that is why women who encourage patriarchy are more dangerous than men who believe they are superior.

Why is it considered acceptable, even by women themselves, for women, their daughter and daughters-in-laws to shoulder not only the burden of household work, as they always have, but now with their professional responsibilities, while their sons and sons-in-law are exempted from the same expectations?

And this is precisely why films like The Great Indian Kitchen unsettle so many people. They force those cushioned by privilege to question it. Two common responses to the film, in particular, stayed with me.

One was, “Women can’t even cook for their own families, but will slave away for random men and call it empowerment.”

What bewilders me is how far from the point one has to go to arrive at such a conclusion. This was never about work. It was always about respect. No woman resents working for the people she loves. But no human being, man or woman, can endure the quiet, everyday disrespect that so many “just housewives” face in Indian households.

The second line that irks me beyond measure is: “Our mothers were the last generation of innocent women.”

Translated plainly, this suggests that they bore every burden, absorbed every form of abuse, and carried entire households on their backs, without ever questioning patriarchy. And that this silence is somehow worthy of reverence. But silence is not innocence. Endurance is not virtue. And suffering should never be romanticised as moral strength.

If anything, the discomfort these films create is evidence of their necessity. Because when equality feels like an attack, it is worth asking who truly benefits from things remaining unchanged.

If masculinity is measured by dominance, then it will always need someone beneath it. But if it is measured by responsibility, care, and shared effort, then it leaves room for dignity, on both sides. And without dignity, there is no place for love. Maybe the question isn’t whether men belong in kitchens, but why equality still feels like defiance in so many homes.