What “Balungan Kere”-Ndarboy Genk Taught Me About Life, Humility, and Finding My Way Back to Spirituality

Medium | 30.12.2025 11:08

What “Balungan Kere”-Ndarboy Genk Taught Me About Life, Humility, and Finding My Way Back to Spirituality

Follow

14 min read

·

1 hour ago

Listen

Share

(Lamongan, December 24, 2025)

Do you believe in destiny? I never really did. But lately, I think… maybe I do

My vacation plan to go to Yogyakarta at the end of this year actually didn’t align with its originally intended. There were several places on my itenerary, yet somehow I didn’t make it to any of them. I ended up skipping my little “plesiran” trip to Gunungkidul because I wasn’t brave enough to go without driver’s license in my wallet. Yaps, it’s simply illegal — and after spending way too long considering the risks, I eventually decided to cancel. Instead, I still go to the beach anyway, even if it was just to feel the Indian Ocean’s waves for a moment. Parangtritis became the best option; because it always offers a new kind of relief, even though I’ve been there countless times.

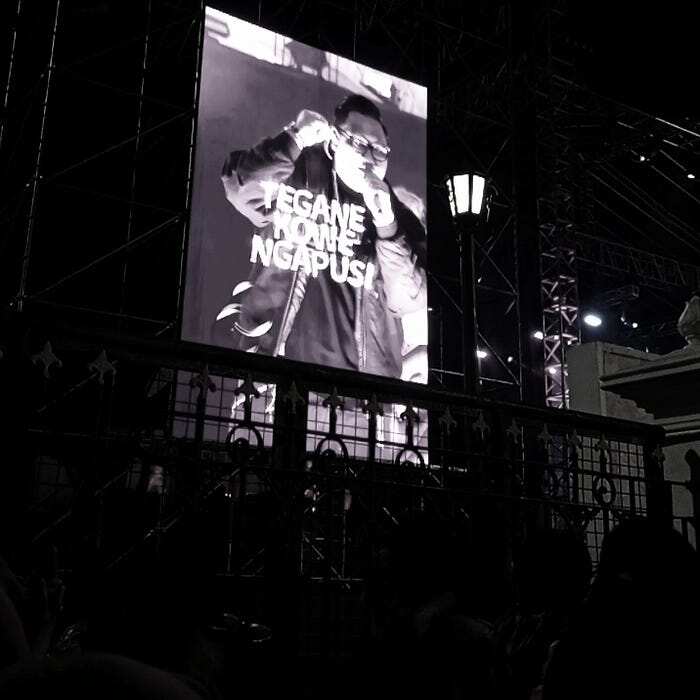

However, this trip also brought something completely unexpected — something I’m genuinely grateful for. One of them was a music concert held to commemorate International Anti-Corruption Day (HAKORDIA 2025) at Titik Nol Kilometer, Yogyakarta. One of the performers at that night was Helarius Daru Indrajaya — the Javanese singer may many people known as Ndarboy Genk. Attending the concert wasn’t part of my plan at all, even when my train pulled into Lempuyangan Station, I had absolutely no clue that the event was taking place.

Then so, on Sunday night, I found myself standing in the middle of that concert. To some of my friends who don’t really know me yet, it probably looked a little bit strange. I imagine it must have been surprising for anyone who only knows the version of me that shares soft, mellow, and Western tunes on Instagram — to suddenly see me swept into a crowd dancing to Javanese Koplo rhythms or (joget), lights flashing, and laughter spilling everywhere. That’s true. It was a different side of me, one I don’t often show, yet somehow felt completely right in that moment. And somehow, there I was, carried by the energy of the crowd, ending up in the very front row as if I belonged there all along.

There’s one thing I still keep hidden, mostly to protect the soft, refined image I’ve built — the fact that I actually have a deep fondness and genuinely enjoy for Javanese Koplo songs. Among them are the songs popularized by Didi Kempot (alm), Denny Caknan, GuyonWaton, Ngatmombilung, NDX AKA, and not least, Ndarboy Genk. Loving this kind of music doesn’t come from any particular reason. I simply enjoy it quietly, letting each lyric unfold slowly, word by word.

In those loud, unpolished lyrics, I found a kind of meaning that felt unexpectedly close to my everyday life — to the reality I see around me. And I understand now why I feel so attached to it; it’s simply because of how deeply my Javanese identity has shaped me, something that has grown with me from the very beginning. Among all those lines, this one stands out to me the most; it’s the part that seems to touch the very edges of my mind, then my conscience:

Kudune kowe ngerteni, (You should’ve realized it,)

Kabeh mung titipane Gusti (that everything we hold is only borrowed from God)

Senajan atiku wis bubrah, (Even when my heart feels torn apart,)

Kandeli nggon(ing) ibadah, (I hold tightly to my worship,)

Gusti sing paringi berkah. (because it is God who grants every blessing.)

The lines above are from “Balungan Kere”, a song written and popularized by Hendra Kumbara and Helarius Daru Indrajaya — or better known as Ndarboy Genk. The song was released around 2019, and might I’ve listened to it countless times since then. But unlike “Mendung Tanpo Udan”, “Koyo Jogja Istimewa”, “Ngawi Nagih Janji”, “Wong Sepele” or “Lanang Tenan”, which often find their way into my repeat playlists, “Balungan Kere” never really stirred my feelings as strongly. Perhaps it had always been there, playing quietly in the background, and its meaning slipping past me, unheard in all the noises of my life.

Even so, singing it directly with the original song writer — in an unfamiliar place, surrounded by strangers — hit me in a completely different way. It might sound a little bit dramatic, but in that moment, I genuinely felt my eyes begin to well up; I was very close to tears in that moment. I can’t quite explain it, but those lyrics touched something at the very core of my being, as if a hidden part of me was struck by the way reality was turned into poetry.

Even though the entire song of “Balungan Kere” doesn’t fully mirroring my own love life story, those certain lines strikes me absolutely — shifting the way I see the world, and life itself. Here are a few precious lessons I’d like to share through this Medium post:

We don’t get to choose the parents we are born to, and for that reason, the life we’re given is something we must learn to accept with a “spacious heart”— understanding that our share in this world is exactly what it is, and that we are meant to find the meaning of “enough” within it.

What Javanese people often call ‘nrima ing pandum’ (ꦤꦿꦶꦩꦲꦶꦁꦥꦤ꧀ꦢꦸꦩ꧀) becomes the clearest expression of how Javanese culture understands and embraces life — accepting one’s portion with grace, without resentment, and with a quiet sense of clarity about what it means to live. Nrima ing pandum reflects an attitude of accepting life’s fate as it comes, a calm submission to whatever circumstances unfold. The attitude of that can be expressed through gratitude and a feeling of contentment with one’s possessions. This teaching is often misunderstood as discouraging hard work and ambition. However, nrima ing pandum should be understood as an attitude adopted after sincere effort has been made and the outcome is entrusted to divine will.

What has long been embedded in their daily lives is a natural inclination to seek blessings in every step they take as they navigate the path of their life. Among Javanese people, we often describe it as ‘berkah’. I’m still not entirely sure how this cultural orientation emerged. Many people believe it is the product of generations of teachings passed down by ancestral leaders and religious figures who have inhabited the land of Java. However, in my own preliminary interpretation, I would argue that this way of life is a product of the social stratification and deeply rooted by Feodalism culture that has defined this land for hundreds, or even thousands of years.

For as long as history remembers, Javanese society have abided by a way of living rooted in acceptance, believing that whatever portion they are given is what they are meant to carry. They have long believed that life marked by lack is not a failure, and standing at the bottom doesn’t erase one’s worth. So they continue walking and walking, even when the end lies close from its starting point. For them, life is about surviving, fulfilling the role they were given, until Gusti (God) calls them back to His embrace. And with that in mind, it becomes important to pause and reflect on the following lessons bellow:

Equity should matter more than equality: when we stop just at tolerance, we risk staying ignorant of the realities others live through. Understanding is what truly bridges the gap.

Understand, because tolerance is ignorance!

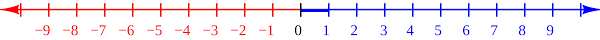

Think of our different backgrounds as a line numbers, centered at 0 (zero). Many people say that this is where everyone begins their journey. But I find myself gently disagreeing. My own experiences have led me to see it differently; I’ve come to understand that not everyone starts at zero. Some begin their journey from numbers below it, maybe -2, -4 or even -7. Likewise, there are those who start above zero — people whose lives are shaped by layers of privilege, beginning their journey at 3, 5, 6.

This is precisely why the process deserves more attention than the result. Rooted in Javanese ways of life, humility emerges from a sincere acceptance of whatever unfolds along our journey. One of the most well-known Javanese Moslem female figures, an author of Hati Suhita’s best selling novel, Ning Khilma Anis, once said that ngalah (to yield) means ng-Allah (to return everything to God). Yielding does not signify lose; rather, it is the conscious act of entrusting all that is beyond our control to the Almighty. That reflection aligns closely with a line preserved in “Balungan Kere” — “kabeh mung titipane Gusti”, which gently reminds us that everything we have is only temporary. With humility, we are asked to realize that nothing truly belongs to us. Sooner or later, all possessions and worldly wealth will eventually return to their Creator. We are not the rightful owners; we are merely entrusted to care for them for a while. Ya, it’s just for a while.

Heartbreak can sometimes act as a gentle rehearsal for finding our way back to spirituality. In “Balungan Kere,” there is a sense of surrender to a destiny that weighs heavily on happiness. Rather than clinging to pain or bitterness, the song turns inward, seeking closeness to God and the blessings that come with it, beyond a romantic fulfillment.

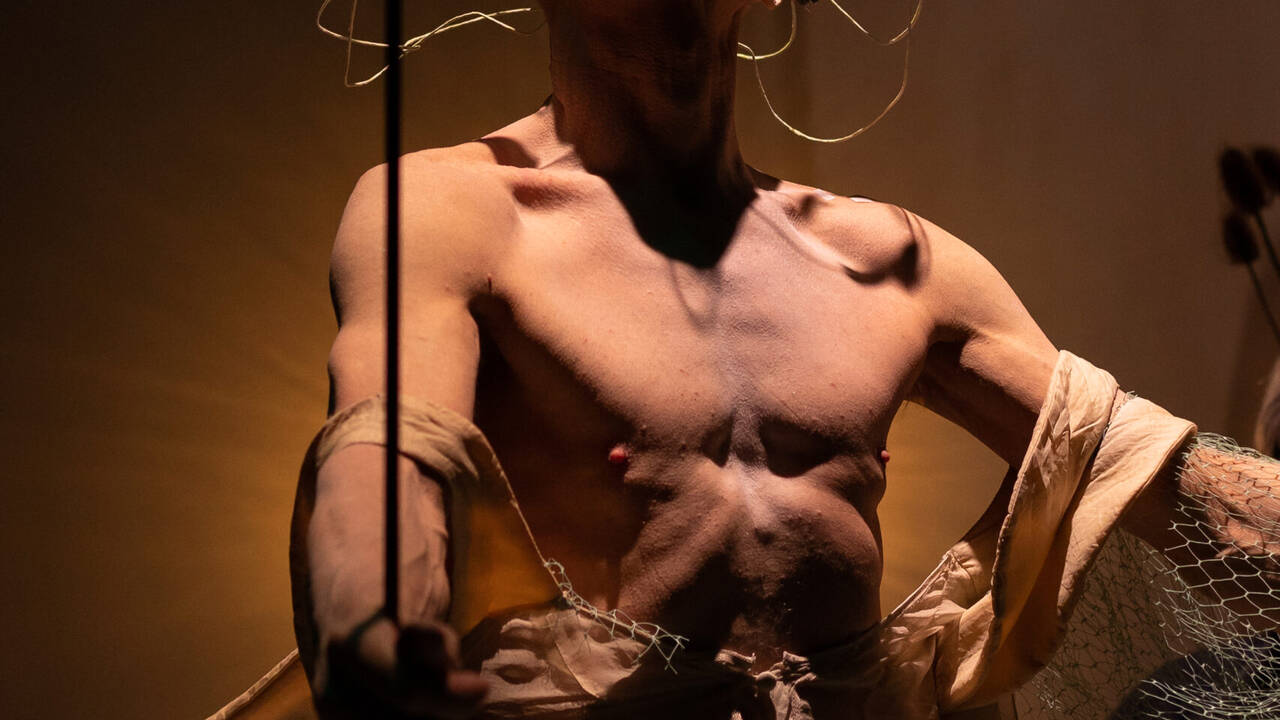

As portrayed in the official music video, Balungan Kere was rooted in a moment of heartbreak. The wound of it reveals comes from a betrayal by someone dearly loved. Instead of hoping for reconciliation, the protagonist entrusts all his feelings to God. Fully aware of his reality, he accepts it with grace, asking for nothing except divine blessing.

Get bridgesinbudapest’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Although a tragic love story like that has never directly intersected with my own life. Still, I can grasp the meaning woven into that song. I read its lyrics through different chapters of my life, letting them resonate in ways beyond heartbreak. Even right now, I think I’m still firmly held by that moment — the moment when the song was performed so vividly right in front of me, and I found myself completely immersed in its melody.

So many things have shifted in the way I see the world since that night. On Monday morning, during my train ride back home to Lamongan, Balungan Kere was the only song looping in my earphones. It continued to linger with me. I found a turning point — one that led me back to a place where I was still a tabula rasa. Only then, I realize that the journey I had walked all this time had quietly matured me far beyond where I was once meant to be. In certain aspects, I sense that the worship I have carried out still falls short of reflecting my commitment to becoming a truly humble person. This is precisely why the line “kandeli nggon(ing) ibadah, Gusti sing paringi berkah” strikes so deeply into my conscience. It made me realize that the direction of my life, both now and ahead, has not been centered on seeking “berkah”, as the song quietly reminds us.

I find myself longing to return — because somewhere along the way, I know I must; I feel the need to come back to where I once was.

There is one thing I tend to overlook. Despite often seeing myself as someone who values to the process, in many ways — after reflecting once more (one of them through Balungan Kere) reveals that I am still, in a lot of aspects, overly attached to results. I often find myself unable to let go of the fixation on outcomes, the constant anticipation of what I might gain every time I choose to do something. After sitting with these thoughts for a long time, I realized that this mindset no longer resonates with the values I want to live by. That is why I feel compelled to search for a turning point.

Then, who could have imagined that my turning point would start with something so ordinary: a simple song, an unplanned encounter, and a spontaneous choice to join the crowd and its shared noises— the restless joy of people simply trying to feel alive.

It was then that I came to understand that ‘ibadah’ and ‘berkah’ exist in a continuous relationship of causality, inseparable from one another. In my personal interpretation, ‘ibadah’ is both an intention and a source of meaning. Our actions, rather than being driven by the pursuit of desired outcomes, should be approached as practices of surrender and humility. Beyond that, I realized that while becoming human is not a matter of choice, but becoming a certain kind of person is something we can consciously pursue.

Life, much like a train journey, each of us would need to decide our destination before choosing the right station to board. Having a preference for where we want to go is a good thing — very good, in fact. However, just as passengers rely on the train crew for the route, we never truly know what we will encounter along the way. If we measure success in life solely by whether or not we arrive at the station we desire, we may only end up collecting tangible things — wealth, intelligence, happiness, power, recognition, and so on. But what often goes unnoticed is something far deeper: the unexpected meaning and usefulness born from our good intentions.

Consider this small example from my own experience. I was profoundly touched by one verse of “Balungan Kere”. Maybe 7 years ago, when Hendra Kumbara and Helarius Daru Indrajaya first wrote that song, could they have known that, if years later, it would reshape someone’s worldview? I doubt it. Perhaps they were simply pouring out their feelings, treating it as part of their work to art and beauty. Maybe their only intention was to make listeners feel represented or at least comforted. Yet, along the way toward that intention, they dedicated their skills, hearts, and thoughts to something sincere. And because of that, the outcome reached far beyond what they might have expected. This impact may not be measurable in concrete terms — such as rising viewer numbers, higher ad revenue, or increasing ticket sales. But the way the perspective and story within “Balungan Kere” will continue to shape my life for the better is, a profound consequence of ‘ibadah’ as intention — the very intention held by the song’s writer.

This is why including ‘ibadah’ as a form of intention in our pursuit of goals is deeply important. Meanwhile, expecting ‘berkah’ as outcomes is not equivalent to aiming for a specific endpoint. It is difficult to put into words, but perhaps this is where the beauty lies: the impact we create for others often extends far beyond our initial goals.

Longing, longing, longing — if life is inseparable from longing, then longing itself is the very breath we live by.

“Berkah” is another form of longing — a longing to returning home. For generations, Javanese people have lived with the awareness that something far greater than material fulfillment: returning to God. They understand that everything they hold in this life (even life itself) is a gift from God: the God who shaped a gentle earth for them to inhabit; who provides food, shelter, and clothing; who breathes love into every inhale they take; who allows joy to visit their days; and who ultimately becomes the place to which they return. In this understanding, God is not seen merely as a ruling entity or a distant controller of the world. Instead, God is understood as tranquility itself — because “peace” is greater than all things, and what they seek, both in living and in dying, is to remain within that peace.

Their acceptance of a simple life — even one marked by scarcity — is not an admission of defeat or powerlessness in the face of the world. It may be that they do not fully realize how unjust the world they live in can be, and they surrender to that injustice with grace. Yet injustice itself is never the center of how they choose to see how the world works. The way they orient their perspectives and set their priorities is consistently shaped by humility and acceptance: such acceptance is the gateway to tranquility — the blessing they see as life’s ultimate aim.

Thinking about this, I’m reminded of a quote from a collection of short stories I read nearly five years ago:

“Kita bertani di pagi hari karena kita rindu pada sujud di kala Dhuhur. Kita mengaji di sore hari karena kita rindu sujud di saat Maghrib. Bekerja itulah selingan kita. Bukan beribadah. Mencari rezeki itulah selingan kita. Sebab intinya adalah sujud dan syukur…” -Puthut EA, (Kelakuan Orang Kaya: Kumpulan Kisah Ringkas yang Mengganggu Pikiran dan Perasaan, 2018)

A way of thinking anchored in the longing for “sujud” frequently leads to a life shaped by gratitude and inner peace. And now, one thing I have finally come to understand is: perhaps humans do not need to position ‘ibadah’ merely as a requirement for the life after death — the eternal hereafter we so often speaks as ‘akhirat’. If many rational-minded people find it difficult to accept what seems irrational — just as I once did — then perhaps the reflections in the paragraphs above can serve as a small shortcut. We do not need the afterlife as our sole reason to live kindly. Berkah— does not have to be imagined as happiness after death. Instead, blessing is our life today: the oxygen we breathe, the food we consume, the work we complete, the prayers we live by, and even the sleep that restores us so we can begin again tomorrow.

Returning to the philosophy of nrima ing pandum that I mentioned earlier: as humans without absolute control, and with all the humility we can carry, we are not meant to expect too much from this life that is, after all, only temporary. Yet between each breath we take — in silent nights, in afternoons drenched with sweat — we keep walking, holding a quiet hope for ease in every step we choose and in every matter we attend to.

We live by prayers — prayers that breathe life into our lives.

This simple life — though often at odds with countless difficulties — still leaves me feeling whole. For in returning to the Javanese identity that has raised and matured me, I wish to live while proudly upholding the values that have shaped the way I see the world. As written popularly in the Kitab Ramalan Jayabaya, that:

Kali ilang kedhunge (A river may one day lose its flow)

Pasar ilang kumandhange (A “traditional” market will lose its clamor)

Wong lanang ilang kaprawirane (Men may lose their bravery, their knightly spirit)

Wong wadon ilang wirange (Women will lose their sense of modesty)

Wong Jowo (ojo nganti) ilang Jawane (And Javanese people — may they never — lose their Javanese soul)

In the end, a longing for humility draws me back to the place where my journey began — empty-handed. Through the care and examples of those closest to me, I grew by learning to mirror their goodness. And indeed, the finest return is to the place where all things originate.

“Balungan Kere” is a doorway, that leads me there. For me, it is far more than a song. Balungan Kere is reflection — a form of contemplation that gently carries everything I have, back to…sumeleh lan sumarah dumateng kersaning Gusti.

*Thank you for reading. May we all find our way back — through longing, surrender, and grace.

Peace be upon this journey,

Alifa B — Passionately wander and wondering a lot.