Expendable Lives: The R-Word, Trump, and the Slow March Toward Dehumanization

Medium | 19.12.2025 21:05

Expendable Lives: The R-Word, Trump, and the Slow March Toward Dehumanization

6 min read

·

1 hour ago

george cassidy payne

When the most powerful person in the world calls a sitting governor the “R-word,” this is not a question of free speech. It is a lesson in who is human, and who is disposable. Words from the Oval Office are never empty; they shape empathy and public perception. When a leader devalues a group of people, society follows, step by step, policy by policy.

Donald Trump is not a private citizen muttering into the void. He wields a global microphone and the authority of the presidency. Every word instructs the nation: who deserves protection, who can be ignored, and who might eventually be abandoned.

BJ Stasio, Peer Specialist with the New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities, explains:

“When national leaders use the R-word casually or as a weapon, it reactivates real harm for people who were once labeled, limited, and underestimated. I know firsthand how the stigma impacts lives.”

Nicole LeBlanc, Disability Employment Consultant and Self-Advocate Advisor, adds:

“Seeing the R-word insult return to everyday language is enraging. People with disabilities want respect, love, acceptance, and access to services that allow us to thrive — not just survive. Using hateful language fuels negative attitudes, health disparities, and higher abuse rates. Respect is not optional.”

Dr. Gary Schaffer, disABLED Professor of School Psychology at Niagara University and Mental Health Counselor, underscores the moral and social danger:

“The R-word is not a neutral term. It is hate speech on full display, reducing a person’s learning and behavioral differences to something negative, laughable, and minimizing their value to society. When the President openly uses the R-word, he signals that discrimination, segregation, and lack of empathy are permissible — not just against the intellectually disabled, but anyone with learning and behavioral differences. This is dangerous given that prior to 1975, many students with disabilities were denied an education because they were viewed as unable to learn.”

Schaffer places this in historical and legal context:

“Presidents have long discriminated against the disabled. William Howard Taft, as Chief Justice, wrote ‘three generations of imbeciles are enough’ in a eugenics-based law upheld by Calvin Coolidge. Nixon vetoed Section 504 twice, sparking state sit-ins. In the 1990s, disabled Americans crawled up the steps of the Capitol in wheelchairs to get the ADA passed. The reintroduction of the R-word continues this pattern: leaders viewing disabled people as disposable.”

Schaffer cites Buck v. Bell (1927), a U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld the forced sterilization of people labeled with mental health conditions, supporting eugenics laws.

“Buck v. Bell has never been formally overturned,” Schaffer adds, “its precedent allowed forced sterilization for people deemed ‘unfit,’ including those with intellectual disabilities. Later cases, like Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942), recognized reproductive rights and discredited Buck’s reasoning, but the decision technically remains-the ability to sterilize the disabled stands. Once language, policy, and public empathy erode, the terrifying possibility of revisiting these practices exists. ”

The erosion of rights is already underway. Federal oversight of special education has weakened. Guidance from the Department of Education has been reduced, and enforcement of IDEA protections undermined. Programs like SOAR — SSI/SSDI Outreach, Access, and Recovery — which help people with severe mental illness and disabilities navigate Social Security benefits, face cuts, leaving participants without income, healthcare, or housing stability. Accessibility measures in White House briefings, including ASL interpretation, have been removed, signaling that the needs of disabled people are optional. Attempts to roll back Section 504 enforcement threaten to let schools segregate students or deny access to education altogether. This was not just one person. Texas v. Becerra (now Texas v. Kennedy), led by 17 states in late 2024, initially sought to declare Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act unconstitutional and eliminate it, though the states later dropped the constitutional challenge but still challenge specic federal rules, especially regarding gender dysphoria. (While the broad effort to end Section 504 was paused or amended, the case highlights ongoing legal battles over disability rights and accommodations, creating uncertainty for protections under this key civil rights law.)

Get George Cassidy Payne’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

This trajectory is clear: first comes rhetoric — the casual or weaponized use of the R-word — dulling empathy. Next comes policy, cuts to protections in schools, dismantling oversight, weakening enforcement. Finally comes institutionalization: segregated classrooms, separate facilities, or outright denial of education. Dehumanized and invisible, disabled people become “expendable,” making historical precedents like Buck v. Bell a latent threat.

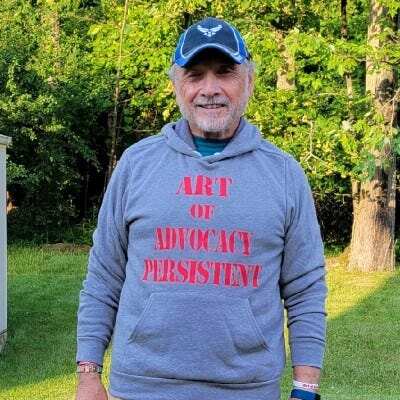

Max Donatelli, USAF Vietnam Veteran and disabilities advocate, recently wrote in The Buffalo News:

“The public disrespect shown by this president to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities is unprecedented. Our country deserves better.”

Emauni Crawley, Behavioral Health Coach and Disability Advocate, is even more blunt: “The manner in which Trump articulates the “R” word is not a result of ignorance. It is an act of perverseness.”

The R-word itself is not new. To retard has existed in English since the late 15th century, meaning “to slow or delay.” By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, retarded became a neutral medical term, considered more humane than “idiot” or “imbecile.” By the 1960s, it became a slur. Today, its casual use signals moral contempt and social devaluation.

Normalizing dehumanizing language causes harm that is personal, systemic, and enduring. Advocacy is not optional, it is a moral and civic responsibility.

Words alone are dangerous — but when paired with policy, the harm compounds. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said:

“It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important.”

Rhetoric that degrades, combined with policies that remove protections, signals which lives are valued, and which are negotiable. Civil rights and access are not abstractions. They are the minimum conditions for respect and inclusion.

Cuts to programs like SOAR, dismantling special education oversight, and removing accessibility measures from White House briefings may seem minor to some. But combined with dehumanizing rhetoric, they form a pattern: erosion of dignity, sentence by sentence, policy by policy, joke by joke. Devaluation begins in language, metastasizes in policy, and ultimately becomes structural violence.

This is not fragility. It is responsibility. A president’s words do more than reveal character; they instruct the nation in who it is permitted to become. When language degrades, paired with hollowed-out protections, dignity ceases to be shared and becomes a privilege rationed by power.

The question is no longer whether such language is legal. It is whether we will accept a politics that treats some people’s humanity as expendable, and whether we will recognize, before it spreads further, that a nation willing to bargain away dignity at the margins will eventually find it gone at the center.

George Cassidy Payne is a journalist and poet based in Rochester, New York. He works as a 988 Suicide Prevention Counselor and as a nonprofit creative strategist and community organizer. With two master’s degrees in the humanities and a background in philosophy, his writing focuses on ethics, disability justice, politics, and the ways language and public policy shape human dignity.