Inside Switzerland's extraordinary medieval library

BBC | 03.02.2026 20:00

The Abbey Library of St Gallen is a Baroque hall of globes, manuscripts and curiosities that has survived, improbably, for 1,300 years.

The church bells were silent and much of the city was still asleep when I arrived at the doors of the abbey in St Gallen. The setting was as expected: a grand sermon in stone, with stark spires and arched windows, marbled cloisters, courtyards and broad steps beckoning visitors inside. Architecture has long been used to inspire faith – but this felt less like discovery than revelation.

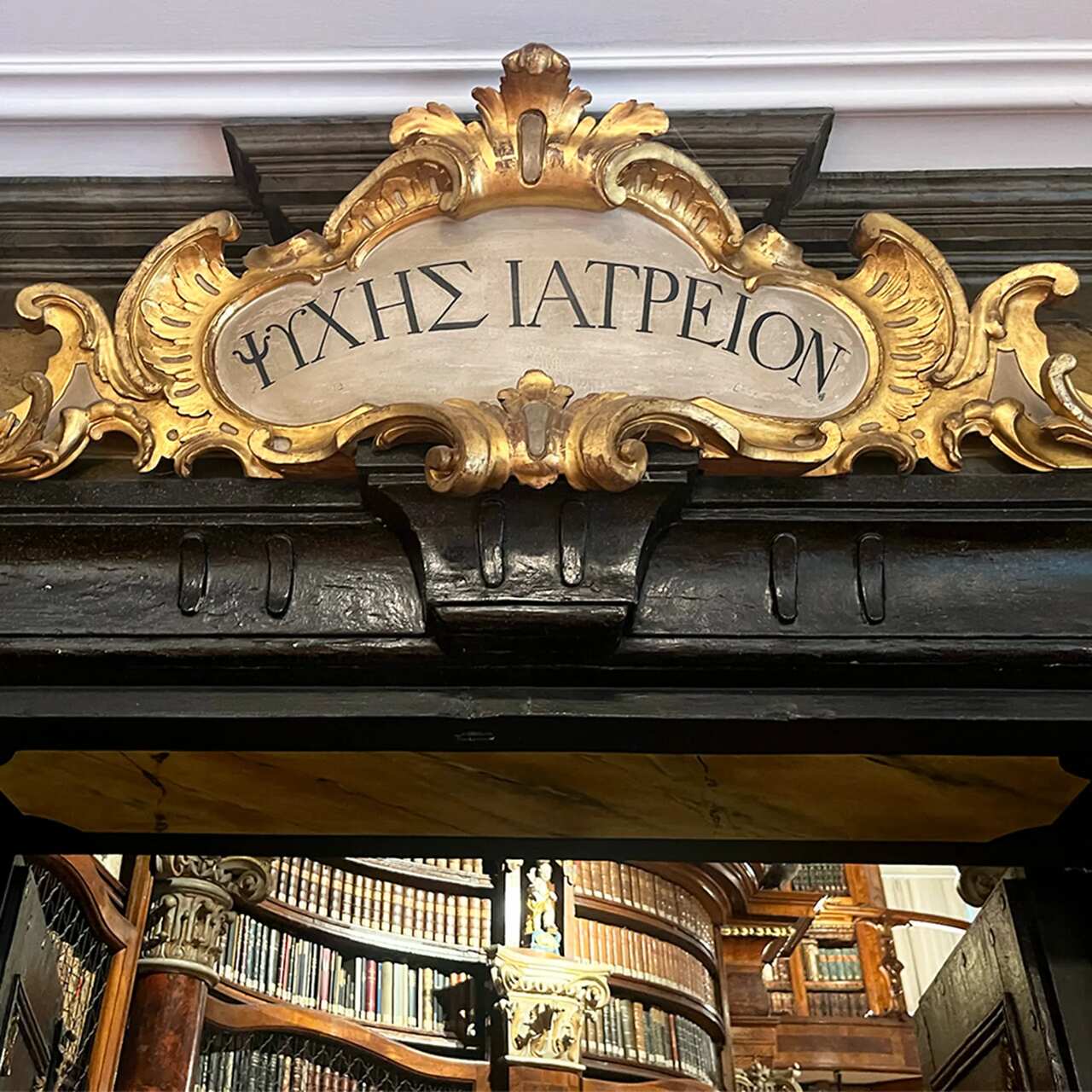

Waiting inside was Albert Holenstein, a bespectacled historian in his 40s. He ushered me along an echoing corridor to an ornate Baroque doorway, beyond which lay a dimly lit room, its curtains pulled tight across rows of windows. Above the entrance, carved into a large Rococo pediment, was a Greek inscription in bold lettering. "Psyches Iatreion," it read. "Healing place of the soul," he whispered.

It was a phrase, I later learnt, associated with the ancient library and scriptorium of King Ramses II in Thebes, Egypt. It sounded like the beginning of a tantalising mystery.

Imagine the world's most fantastical library. What would it look like? You might envisage a grand hall lined with antique reading desks and floor-to-ceiling bookcases. Or maybe an elaborate collection that carries the dream-like atmosphere of a fantasy novel. Perhaps, one like Bodley's Library in Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, itself inspired by the great Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford. Or one more like the transcendent, wizardly library of Hogwarts from J K Rowling's Harry Potter saga (indeed, Duke Humfrey's Library, the oldest reading room at the Bodleian Library, served as the production location for the library in the Potter films).

The Abbey Library of St Gallen in eastern Switzerland befits the awe and wonder of many of these descriptions. With intricate woodwork, balconied gantries and vast stockpiles of leather-bound tomes, it is one of the world's best-preserved Baroque libraries. And for centuries, Switzerland's largest and oldest monastery library has been regarded as one of Europe's intellectual treasures.

Holenstein and I entered and immediately stood beneath an elaborate ceiling fresco surrounded by terrestrial and celestial globes, Egyptian mummies and cabinets of curiosities, each filled with ornamental treasures from far and wide: silver knives in leather sheaths from Turkey; miniature shoes from Indonesia; fossils, shells and coins from all four points of the compass. Our visit began in the 21st Century, but within moments we'd been whisked back to the Middle Ages.

"Incredible, isn't it?" said Holenstein, director of the Centre of Ecclesiastical Cultural Heritage at the Abbey Library of St Gallen. "You can't help but marvel at the collection."

Scanning the shelves, I noted works of the fathers of the church, liturgical books and saints' biographies, but also texts about law, music, medicine, astronomy, grammar, arithmetic, rhetoric and secular poetry.

"It is an abundant source of knowledge," Holenstein continued. "The monastery was not only a religious place, but also an educational institution and repository of knowledge, which helps explain the depth of our collection."

Apart from its vast tomes, what makes the library so compelling is its age. Its origins date to the early 7th Century, when the Irish missionary Saint Gall founded a hermitage on this site, later giving rise to the abbey. Although the original library was replaced in 1767 by the present Baroque hall, the continuity is remarkable. Today, the library and its two vast underground depositories contain one of the world's most valuable bodies of written heritage, including 160,000 manuscripts and early printed works, including more than 2,100 medieval codices – some 400 of them written before the year 1000.

Among these are the largest assemblage of Irish manuscripts in mainland Europe, brought to St Gallen in the early Middle Ages when Irish pilgrims visited on their way to Rome, leaving gifts at St Gall's tomb. Equally rich for academics is the archive of old High German manuscripts, containing the earliest examples of the language preserved in writing. Every book has its own story, and together they express the spiritual and sublime power of the written word.

The other most impressive thing about the library, according to Holenstein, is how the Abbey Library of St Gallen managed to survive centuries of religious and political upheaval. In England, Wales and Ireland in the mid-16th Century, Henry VIII dismantled more than 800 monasteries to seize their wealth, with library collections confiscated and redistributed. During the French Revolution and German mediatisation at the turn of the 18th century, church property was again seized and nationalised.

But thanks to the foresight of St Gallen's librarians, the holdings survived the Protestant Reformation unscathed. Even between 1797 and 1805, when the abbey itself was dissolved, its holdings were fiercely guarded, transferred and rescued by the Catholic denomination within the newly founded Canton of St Gallen.

"You could say St Gallen has had a lot of luck," said Holenstein. "Many of our original manuscripts are still in the place where they have been written, studied and conserved for thousands of years."

If you have a taste for the Baroque, then know that the Abbey Library of St Gallen is no one-off in Central Europe. Switzerland's other grand library can be found at Einsiedeln within a 10th-Century Benedictine monastery; while the Melk Abbey Library, which overlooks the River Danube west of Vienna, is another extraordinary temple of literature.

More like this:

Equally daunting in Austria, Kremsmünster Abbey Library near Salzburg was built between 1680 and 1689, nearly a century before St Gallen's. However, the official title of the world's largest monastic library goes to Styria's Admont Abbey's Baroque storehouse of more than 70,000 volumes. It's hard not to be gripped by the majesty of it all.

But St Gallen's library is only one part of the abbey's legacy. The pedestrianised Old Town is built up around the former monastery, and feels like a living museum of quadrangles, religious cloisters, cobblestoned streets and Erststockbeizen, first-floor taverns first popularised by the monks and the pilgrims who followed.

Built between five and six centuries ago, so well-worn they have tilting floors and ceilings and warped gothic timber beams, these restaurants are secret sanctuaries in their own right. One of these, Michelin-star rated Zum Goldenen Schäfli, is hidden inside a former butchers' guildhall. Other highlights in keeping with the medieval times include Wirtschaft zur alten Post, Weinstube zum Bäumli and Genussmanufaktur Neubad.

Alamy

AlamyBeyond the town centre, the Drei Weieren lakes, created by the monastery in the 17th Century to meet their growing water needs, now serve a wild swimming sanctuaries with Art Nouveau bathhouses on a high plateau above the city.

Today, around 190,000 people visit the abbey library each year, far outnumbering the dwindling community of religious pilgrims. Tourism has become essential to maintaining the site – a shift reflected in the library's gift shop, which now sells everything from locally branded cheese fondue to bird seed and slow-brewed beer.

Does that threaten the library's spirit? Holenstein is pragmatic. "The meeting of the spiritual and secular life brings out a conflict in an active monastery," he said. "By their very nature, monasteries and abbeys are restrictive places. But many are struggling and tourism is one of the solutions in helping keep these cultural institutions alive."

Even so, there is a natural restriction for visitors to the abbey, and it is an unusual one. At the library's ornate Baroque doorway are rows of felt pilgrim slippers, which must be worn to protect the varnished wooden floor. To limit numbers and help with conservation, there will only ever be 100 pairs.

In an age that prizes digital media, St Gallen's Abbey Library is a reminder that however disconnected you might feel from AI, e-books, online archives, virtual assistants and personalised recommendations, you can still step into a world of knowledge in the middle of an ancient abbey. How extraordinary that the words and memories of the voices from the past continue to speak to us, in our present, in the 21st Century.

This sanctuary for the soul is indeed a heavenly place.