Why We’re Becoming Increasingly Lonely

Medium | 24.12.2025 19:35

Why We’re Becoming Increasingly Lonely

Why young people are spending more time alone

7 min read

·

1 hour ago

--

Listen

Share

A few days ago, while walking through the neighborhood at sunset, I passed by a sports complex.

There were benches, trees, a basketball court, soccer fields… and almost no one. Only a few people were playing; a few small groups were sitting together, looking at their phones while talking. It felt strange to see so few people on a day and at a time when I remembered the place being full of people in my childhood.

It was a space designed for meeting others that had lost its reason for being.

That left me thinking…

It’s not just that young people go out less than before.

It’s that they’re stopping seeing each other.

And that change comes with a cost we’re only just beginning to see. If this increasingly isolated and digital life we live feels exhausting to you, today you’ll discover what’s really happening — and what effects it has (and will have) on the well-being of new generations.

The disappearance of meeting up

The problem isn’t being alone.

It’s the disappearance of face-to-face encounters.

For a while, the idea of a “loneliness epidemic” was met with skepticism. It was hard to prove. Loneliness leaves no physical trace, isn’t easily measured, and for years there was barely any reliable historical data to compare against. It was reasonable to wonder whether we were facing a real change or simply a better way of measuring something that had always been there (Burn-Murdoch, 2025).

That doubt was reasonable.

What’s no longer so easy is to keep ignoring it.

In recent years, many sources have begun to converge in the same direction. Time-use analyses reveal a sustained decline in in-person socialization. And mental health problems are growing precisely in the same age groups where isolation is increasing — not among older adults.

It’s not definitive proof of causality, but it is a relationship that’s hard to ignore.

When so many lines of research start telling the same story, it’s worth listening to what they have to say…

The decline of in-person socialization

Youth social life hasn’t disappeared, but it has changed very quickly.

Data from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe show a sharp drop in how often adolescents and young adults interact in person with friends, family, or peers. I’m not talking about partying less — it’s something more basic: seeing each other, sharing space, being together without a screen in between. In Europe, the proportion of young people who don’t socialize even once a week has gone from 1 in 10 to 1 in 4 in a decade (Burn-Murdoch, 2025).

That’s a huge cultural shift.

But the generational comparison makes it even more striking.

Today, a 20-year-old socializes as much as a 30-year-old did two decades ago. In other words, someone who is 20 today socializes like a 30-year-old adult did in the early 2000s. This means fewer meetups and shorter ones, fewer plans with friends, fewer shared activities.

And that void doesn’t stay empty: it gets filled with other things…

Technology: your new best friend (and almost the only one)

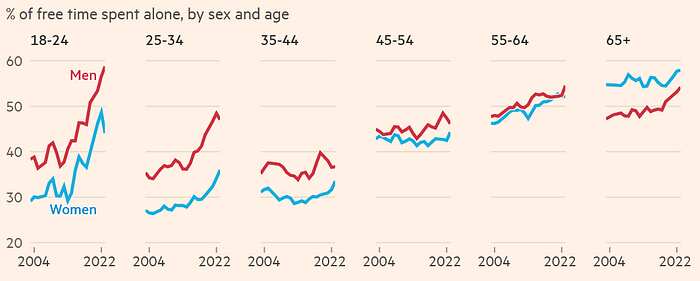

The change didn’t happen all at once, but it was very precise in timing.

The spread of mobile phones and social media coincides almost exactly with the period when in-person socialization begins to decline and time spent alone skyrockets. It’s not a direct accusation (correlation does not imply causation), but it is a correlation that’s hard to ignore (Burn-Murdoch, 2025).

Something stopped happening outside, in public spaces.

And something started to take its place inside a screen.

Time-use studies clearly show which activities replaced in-person social life. Hours spent playing video games, scrolling, consuming social media content, and jumping from stimulus to stimulus in front of screens — alone in a room — grew significantly.

And here comes an uncomfortable fact.

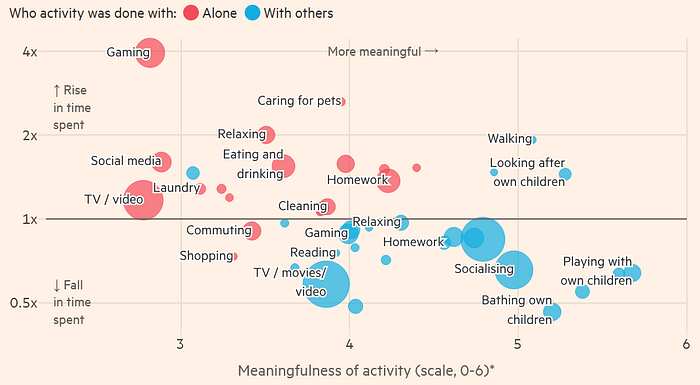

When young people aged 18 to 29 are asked how they feel while doing these activities, they themselves rate them as the least meaningful parts of their day. The ones that leave the least sense of purpose. The ones that bring the least satisfaction afterward. The chart you saw reflects their own perception of their habits.

It’s not a worried adult saying this.

Get Mental Garden’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Subscribe

Subscribe

It’s the people who spend the most time there (Burn-Murdoch, 2025).

They’re aware that something isn’t working, but they’re trapped in the loop.

Technology is not the enemy.

The problem arises when it replaces social life instead of complementing direct interaction. A video call can maintain a bond, but it can’t replace the emotional density of sharing space, laughter, and activities.

And that difference changes everything.

Never so connected… and so little together

There’s one variable that fits almost all the pieces of the puzzle: time spent alone.

The time-use data we saw show that adolescents and young adults are spending more and more hours of the day alone — but not inactive in contemplative silence. On the contrary: frenetic activity involving video games, social media, videos, and endless scrolling.

What stands out is the loneliness factor.

Doing the same activity alone is associated with lower happiness and a weaker sense of purpose than doing it with others. It doesn’t matter whether it’s eating, walking, watching a show, or playing video games. Company enhances everything. And when these data are combined with changes in life satisfaction among young people between 2010 and 2023, loneliness and activities help explain why satisfaction declined.

The problem isn’t being alone sometimes — it’s turning it into the default way of doing everything.

The chart on the right: A model was built to predict the outcome. People were asked to rate each activity based on their sense of purpose and happiness while doing it. The activities were part of Americans’ routines in 2010 and 2023.

The model and the reality observed in 2023 are quite similar. It was predictable.

- In 2010, 38% of adolescents and young adults were satisfied with their lives.

- In 2023, 25% of adolescents and young adults were satisfied with their lives.

And these data matter.

Adolescence and youth are social stages and sensitive periods of psychological development. Scientific evidence shows that the young brain is especially sensitive to social interaction, validation within groups, and a sense of belonging. Social deprivation during these stages increases the risk of emotional problems and lower well-being (Burn-Murdoch, 2025).

The damage is usually not immediate, but it is cumulative.

Like the metaphor of the frog in slowly heating water — each small change seems tolerable until it ends up burned in boiling water without realizing it. Fewer meetups this week. A bit more time online. Another plan gets canceled and you stay home scrolling through social media for hours.

Nothing dramatic on its own. All harmful together.

The good news is that this isn’t irreversible.

Understanding what’s happening is the first step toward designing family, educational, urban, and digital environments that once again make human connection easier. The great paradox is that we’ve never been more connected — yet no one is having physical encounters.

Everyone is online while the parks are empty.

Want to know more? Here are 3 related ideas to explore further:

- Why are we so tired?

- Why is it getting harder and harder to concentrate?

- Digital minimalism: How to reclaim time and calm in a fast-paced world

✍️ Your turn: If you looked at your week from the outside, how much of your social time happens in physical presence… and how much in digital solitude?

💭 Quote of the day: “We are wired for connection. But the key is that, at any given moment, it has to be real.” — Brené Brown, Braving the Wilderness

🌱 Here I plant ideas. In the newsletter, I make them grow.

Daily insights on self-development, writing, and psychology — straight to your inbox. If you liked this, you’ll love the newsletter. 🌿📩

👉 Join 48.000+ readers: Mental Garden

See you in the next letter, take care! 👋

References 📚

- Burn-Murdoch, J. (2025). Young people are hanging out less — it may be harming their mental health. Financial Times. URL