Global temperatures dipped in 2025 but more heat records on way, scientists warn

BBC | 14.01.2026 10:44

Global temperatures in 2025 did not quite reach the heights of 2024, thanks to the cooling influence of the natural La Niña weather pattern in the Pacific, new data from the European Copernicus climate service and the Met Office shows.

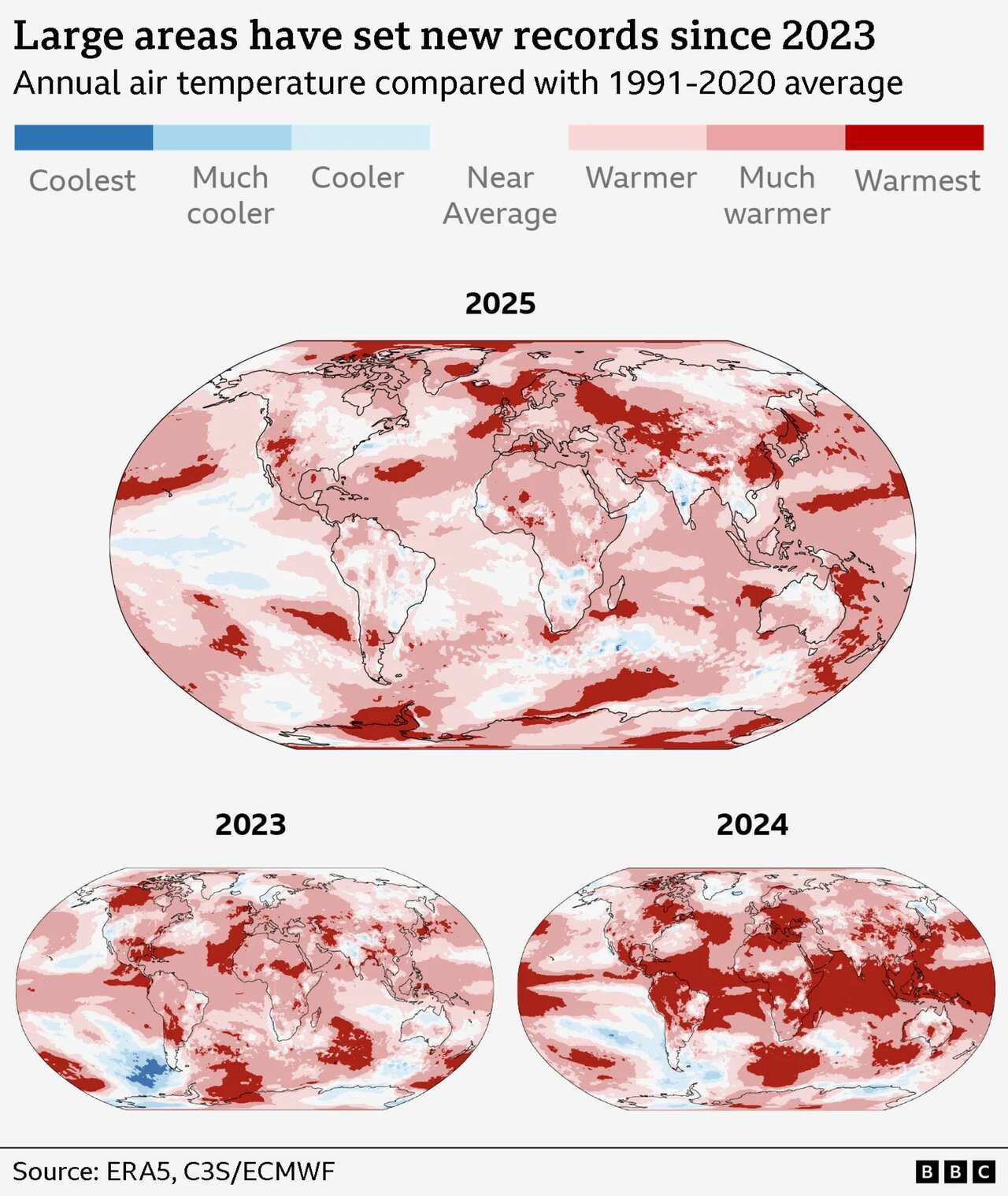

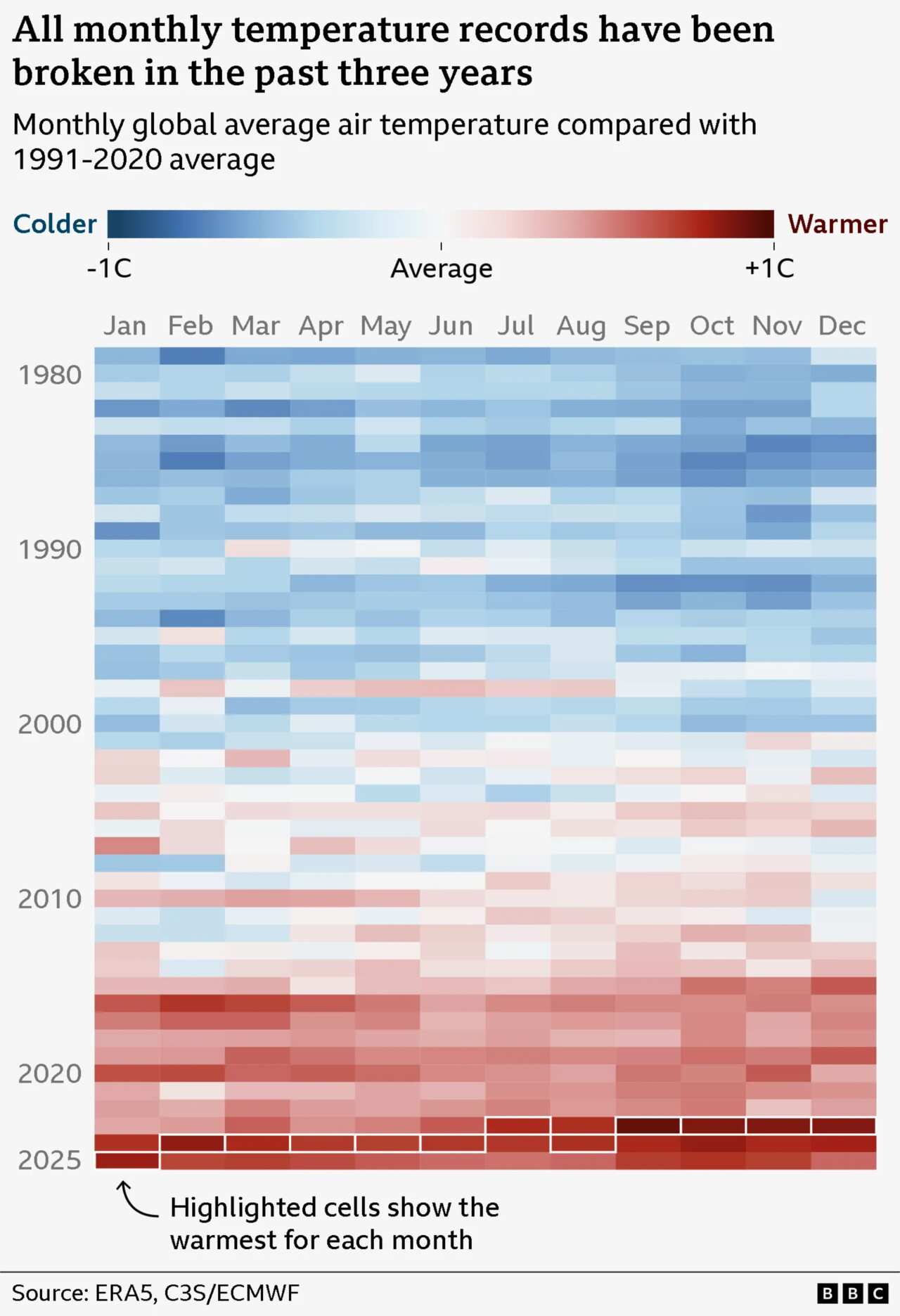

But the last three years were the world's warmest ever recorded, bringing the planet closer to breaching international climate targets.

Despite natural cooling from La Niña, 2025 was still much warmer than temperatures even a decade ago, as humanity's carbon emissions continue to heat the planet.

That will inevitably lead to further temperature records – and worsening weather extremes – unless emissions are sharply reduced, scientists warn.

"If we go twenty years into the future and we look back at this period of the mid-2020s, we will see these years as relatively cool," said Dr Samantha Burgess, deputy director of Copernicus.

The global average temperature in 2025 was more than 1.4C above "pre-industrial" levels of the late 1800s - before humanity started burning large amounts of fossil fuels - according to Copernicus and Met Office data.

The precise figures vary slightly between major climate groups, owing mainly to small differences in how the pre-industrial temperature is calculated. But there is no debate about the world's long-term warming trend.

"We understand very well that if we continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the concentrations of those gases increase in the atmosphere, and the planet responds by warming," explained Prof Rowan Sutton, director of the Met Office Hadley Centre.

Last year might not have been the hottest on record worldwide but extreme weather events linked to global warming continued.

The Los Angeles fires in January and Hurricane Melissa in October were just two examples of extreme weather that scientists have found were likely fuelled to some extent by climate change.

The continued warmth brings the world closer to breaching the international target to try to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

That was agreed by nearly 200 countries in 2015, with the aim of avoiding some of the much more severe consequences of climate change that 2C of warming would bring.

"Looking at the most recent data, it looks like we'll exceed that 1.5 degree level of long-term warming by the end of this decade," said Burgess.

While long-term warming is the result of human activities, individual years can be slightly warmer or cooler because of natural variability.

One such variable is the switch between the weather patterns El Niño and La Niña.

They primarily affect weather in the Pacific but have a knock-on effect on temperatures worldwide. El Niño years tend to be warmer as a global average, while La Niña years are typically cooler.

El Niño boosted temperatures in the world's warmest year, 2024, as well as to a lesser extent 2023.

The return of La Niña conditions is thought to have suppressed warmth in 2025. But the fact that temperatures have remained so high in a La Niña year "is a little worrying", according to Dr Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth in the US.

The last three years have seen global temperature records broken by significant margins. As the chart below shows, new records for each month of the year have been set since 2023.

The size of the jump in temperatures in 2023 surprised many scientists – sparking speculation about what might be behind the surge, in addition to carbon emissions and El Niño.

Theories include changes to clouds and tiny particles called aerosols, which appear to be reflecting less of the Sun's energy back into space.

The persistence of extreme warmth into 2025 "suggests that there might be some mysteries that we haven't fully solved", said Hausfather.

"We are seeing rapid warming at the upper end of our longer-term expectations," agreed Sutton.

But whether the last three years have significiant implications for the longer term "is not yet clear", he added, with more data needed before making firm conclusions.

While scientists expect more records to be broken in the years ahead, they emphasise that the future impacts of climate change are not set in stone.

"We can strongly affect what happens," said Sutton, "both by mitigating climate change - that's by cutting greenhouse gas emissions to stabilise warming - and of course also by adapting, by making society more resilient to ongoing changes."

Additional reporting by Jess Carr

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.