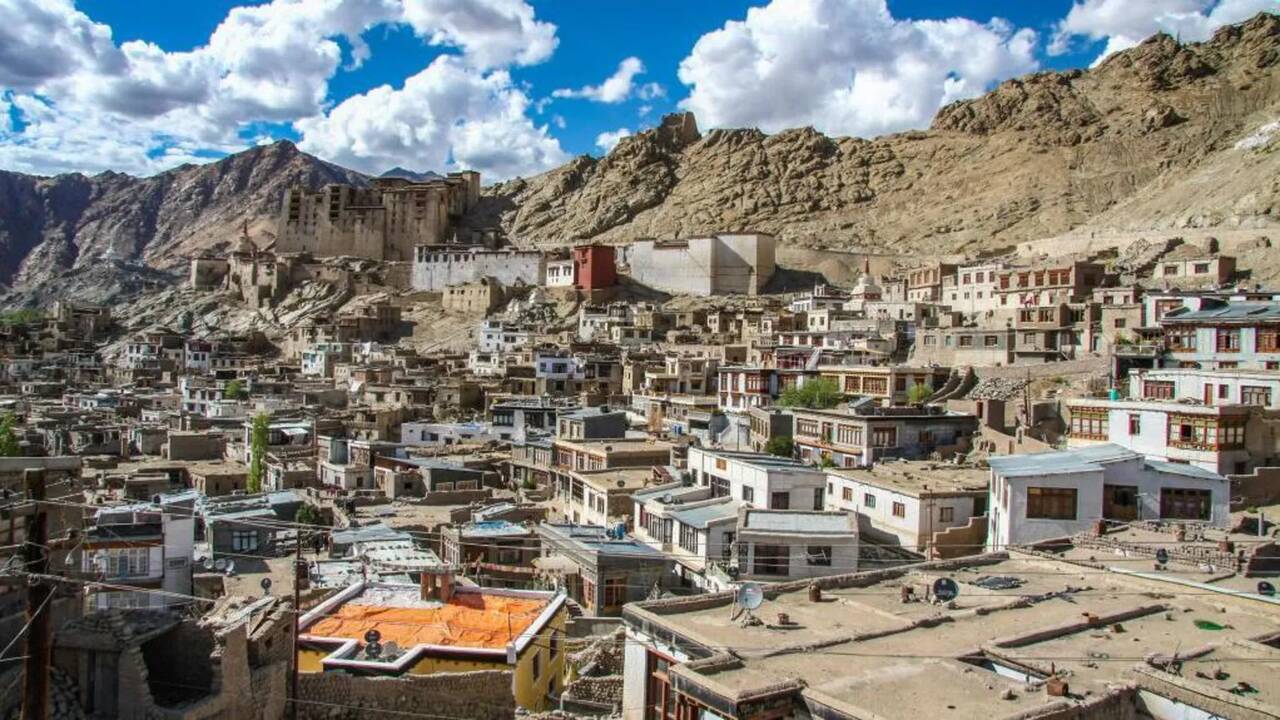

Himalayas bare and rocky after reduced winter snowfall, scientists warn

BBC | 12.01.2026 07:38

Himalayas bare and rocky after reduced winter snowfall, scientists warn

Much less winter snow is falling on the Himalayas, leaving the mountains bare and rocky in many parts of the region in a season when they should be snow-clad, meteorologists have said.

They say most winters in the last five years have seen a drop compared to average snowfall between 1980 and 2020.

Rising temperature also means what little snow falls melts very quickly and some lower-elevation areas are also seeing more rain and less snow, which is at least in part due to global warming, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and other scientific reports.

Studies have also shown there is now what is known as "snow drought" during winter in many parts of the Himalayan region.

Accelerated melting of glaciers in the wake of global warming has long been a major crisis facing India's Himalayan states and other countries in the region. This dwindling snowfall during winter is making matters worse, experts have told the BBC.

They say that the reduction in ice and snow will not only change how the Himalayas look, it will also impact the lives of hundreds of millions of people and many ecosystems in the region.

As temperatures rise in spring, snow accumulated during winter melts and the runoff feeds river systems. This snowmelt is a crucial source for the region's rivers and streams, supplying water for drinking, irrigation and hydropower.

Apart from impacting the water supply, less winter precipitation - rainfall in the lowlands and snowfall on the mountains - also means the region risks being gutted by forest fires due to dry conditions, experts said.

They add that vanishing glaciers and declining snowfall destabilise mountains as they lose the ice and snow that act as cement to keep them intact. Disasters like rockfalls, landslides, glacial lakes bursting out and devastating debris flows are already becoming more common.

So, how serious is the drop in snowfall?

The Indian Meteorological Department recorded no precipitation - rainfall and snowfall - in almost all of northern India in December.

The weather department says there is a high possibility that many parts of northwest India, including Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh states, and the federally-administered territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, will see 86% less than long period average (LPA) rainfall and snowfall between January and March.

LPA is the rainfall or snow recorded over a region over 30 to 50 years and use its average to classify current weather as normal, excess or deficient.

According to the weather department, north India's LPA rainfall between 1971 and 2020 was 184.3 millimetre.

Meteorologists say the sharp drop in precipitation is not just a one-off thing.

"There is now strong evidence across different datasets that winter precipitation in the Himalayas is indeed decreasing," said Kieran Hunt, principal research fellow in tropical meteorology at University of Reading in the UK.

A study Hunt co-authored and published in 2025 has included four different datasets between 1980 and 2021, and they all show a decrease in precipitation in the western and part of the central Himalayas.

Using datasets from ERA-5 (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis), Hemant Singh, a research fellow with the Indian Institute of Technology in Jammu, says snowfall in the north western Himalayas has decreased by 25% in the past five years compared to 40-year long-term average (1980-2020).

Meteorologists say Nepal, within which the central Himalayas is situated, is also seeing a significant drop in winter precipitation.

"Nepal has seen zero rainfall since October, and it seems the rest of this winter will remain largely dry. This has been the case more or less in all the winters in the last five years," says Binod Pokharel, associate professor of meteorology at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu.

Meteorologists, however, also add that there have been heavy snowfalls during some winters in recent years, but these have been isolated, extreme events rather than the evenly distributed precipitation of past winters.

Another way scientists assess the decrease in snowfall is by measuring how much snow is accumulated on the mountains, and how much of that remains for a period of time on the ground without melting: known as snow-persistence.

The 2024-2025 winter saw a 23-year record low of nearly 24% below-normal snow persistence, according to a report by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

It said four of the past five winters between 2020 and 2025 saw below-normal snow persistence in the Hindu Kush Himalaya region.

"This is generally understood to be consistent with decreased winter precipitation anomalies and snowfall in a significant portion of the HKH (Hindu Kush Himalaya) region," said Sravan Shrestha, senior associate, remote sensing and geoinformation with ICIMOD.

A study Singh with the IIT in Jammu co-authored and published in 2025 shows that the Himalayan region is now increasingly seeing snow droughts – snow becoming significantly scarce – particularly between 3,000 and 6,000m elevations.

"With snowmelt contributing about a fourth of the total annual runoff of 12 major river basins in the region, on average, anomalies in seasonal snow persistence affect water security of nearly two billion people across these river basins," the ICIMOD snow update report warns.

Melting Himalayan glaciers pose long-term water scarcity risks, while reduced snowfall and faster snowmelt threaten near-term water supplies, experts warn.

Most meteorologists cite weakening westerly disturbances – low-pressure systems from the Mediterranean carrying cold air – as a key reason for reduced rainfall and occasional snow during winter in northern India, Pakistan, and Nepal.

They say in the past, the westerly disturbances brought significant rain and snowfall during winter, which helped crops and replenished snow on the mountains.

Studies are mixed: some report changes in westerly disturbances, while others find no significant shift.

"However, we know that the change in winter precipitation must be related to westerly disturbances, since they are responsible for the majority of winter precipitation across the Himalayas," said Hunt.

"We think two things are happening here: westerly disturbances are becoming weaker, and with less certainty, tracking slightly further northward. Both of these inhibit their ability to pick up moisture from the Arabian Sea, resulting in weaker precipitation," he added.

The Indian weather department has labelled the westerly disturbance north India has experienced so far this winter as "feeble" because it could generate very nominal rainfall and snowfall.

Scientists may sooner or later find out what is behind the decrease in winter precipitation.

But what is already becoming clear is that the Himalayan region now faces a double trouble.

Just when it is rapidly losing its glaciers and icefields, it has also begun to get less snow. This combination, experts warn, will have huge consequences.